A single session of resistance exercise stimulates muscle protein synthesis. Over time, resistance training can result in muscle mass gains.

Protein intake also stimulates muscle protein synthesis (Trommelen, 2020). Therefore, protein intake can further improve training-induced muscle mass gains.

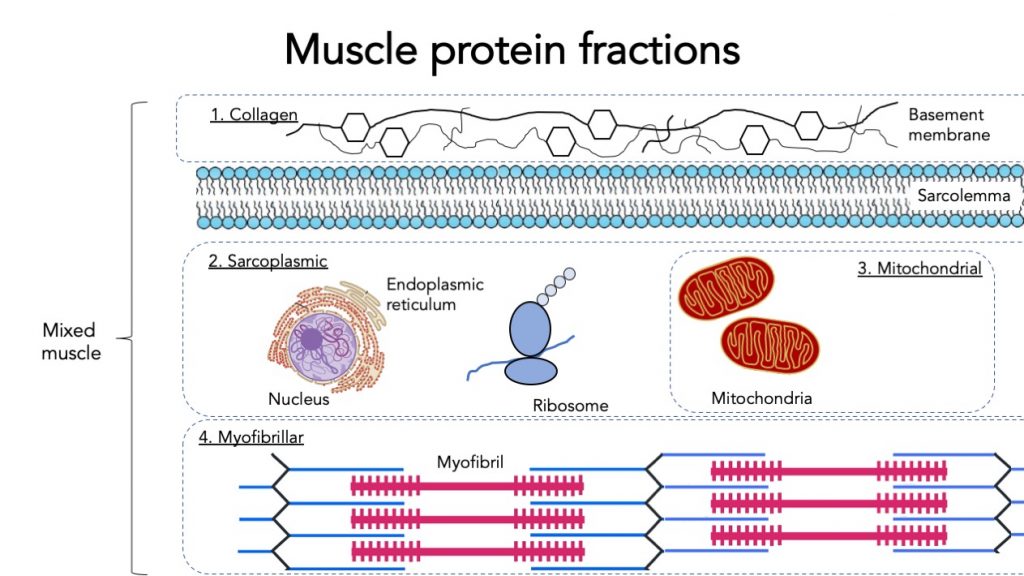

Muscle proteins can be classified into several categories, most notably:

- Myofibrillar protein

- Sarcoplasmic protein

- Mitochondrial protein

- Connective tissue (collagen) protein

- (All muscle protein combined is called mixed muscle protein)

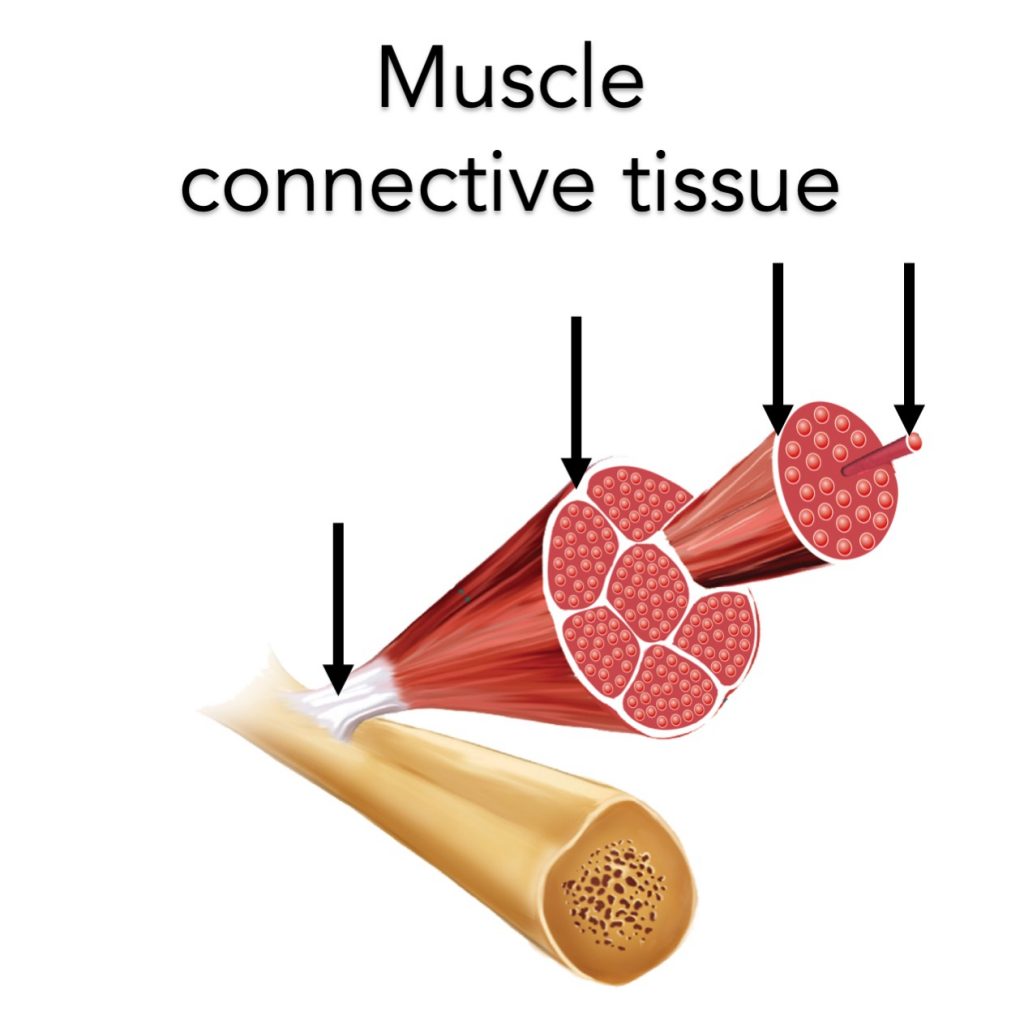

Myofibrillar proteins are the contractile proteins that generate muscle force. This force must be transferred to the bone to allow a dynamic muscle contraction. Intra- and extra-muscular connective tissue proteins help with this force transfer.

As resistance training results in increases in the size and strength of the myofibrillar proteins, it seems evident that muscle connective tissue proteins need to adapt to keep up.

Indeed, several studies have shown that resistance exercise stimulates intramusclar connective tissue protein synthesis.

However, can post-exercise intramuscular connective tissue protein synthesis be further enhanced by protein ingestion (as is the case for myofibrillar protein synthesis?)

Most studies suggest it does not. But one study observed a possible effect (Holm, 2017).

In that study, subjects performed exercise and then received ~18 g whey protein. Protein intake did not stimulate muscle connective tissue protein synthesis in the first 3 hours after protein ingestion, but it did appear to stimulate muscle connective tissue synthesis in the 3-5 h period after protein ingestion.

Based on this study, it could be speculated that protein ingestion may have a delayed effect on muscle connective tissue protein synthesis.

If there is indeed a delayed effect, you want to measure muscle connective tissue protein synthesis over a longer period so you don’t stop your measurement just when the effect starts happening.

Therefore, we designed a study to investigate the impact of protein synthesis over a longer period than previous studies.

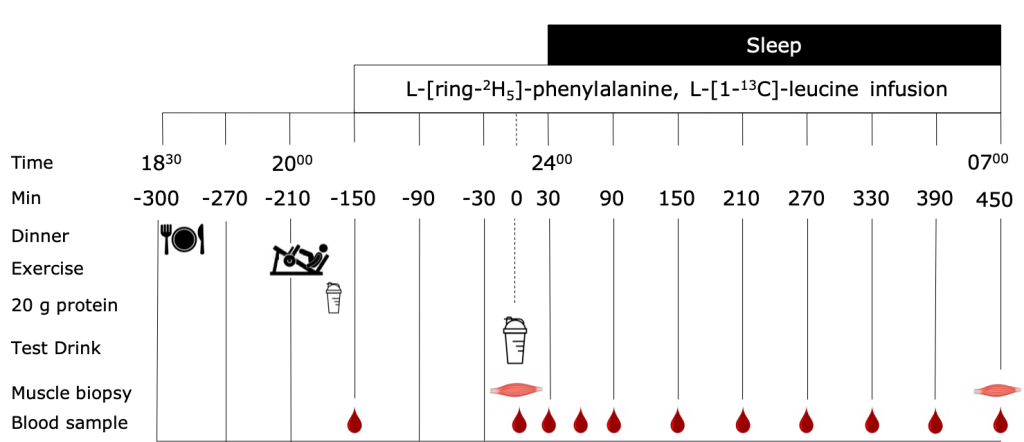

We investigated the impact of:

- EX: exercise in the evening (19:45 h)

- PRO: pre-sleep protein ingestion (23:30 h)

- EX+PRO: combination of exercise in the evening and pre-sleep protein ingestion

We measured muscle protein synthesis during a 7.5 h overnight period after protein ingestion.

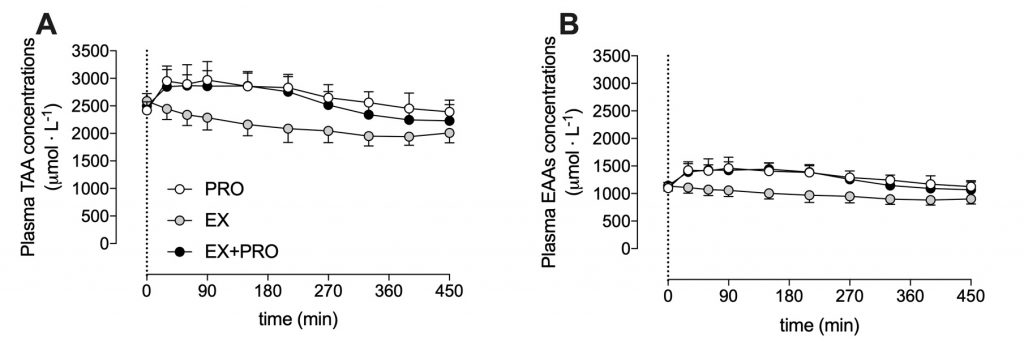

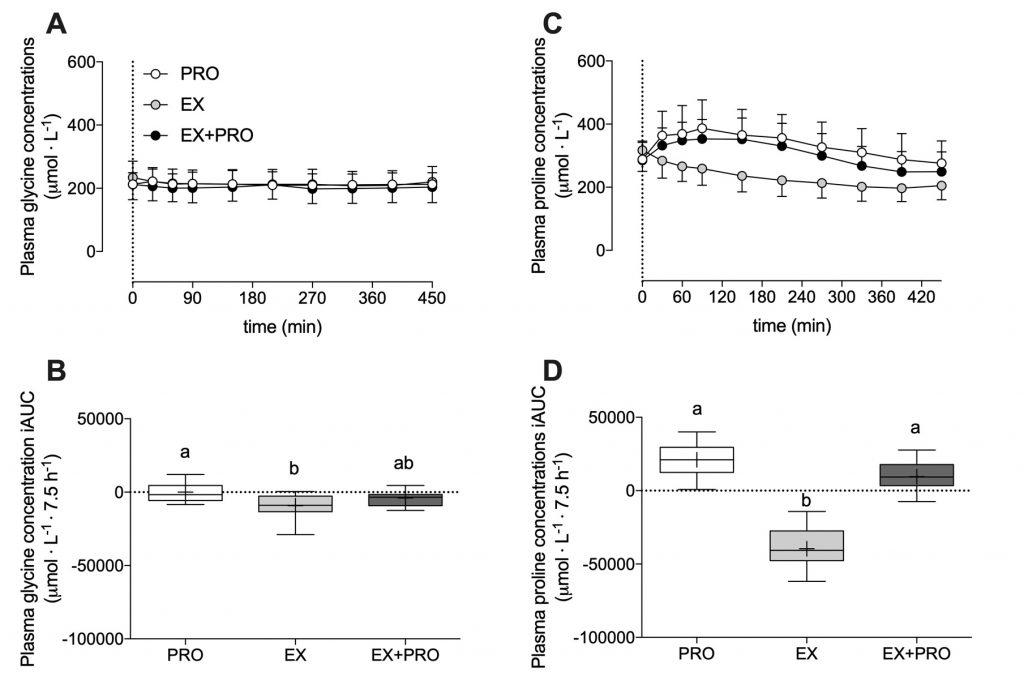

The ingestion of 30 g casein protein substantially increased plasma total amino acids levels.

This response was also seen for proline, but not for glycine. Proline and glycine are two main amino acids in connective tissue.

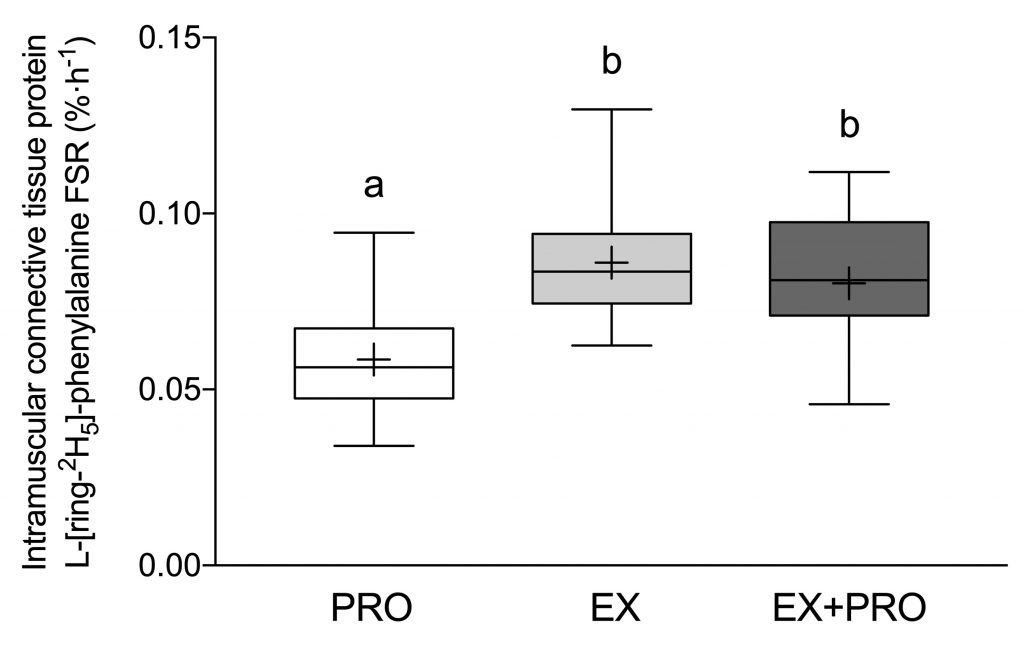

As expected, the two treatments that performed exercise had higher intramuscular connective tissue protein synthesis rates compared to the group that didn’t. However, protein did not appear to have an added effect on top of exercise.

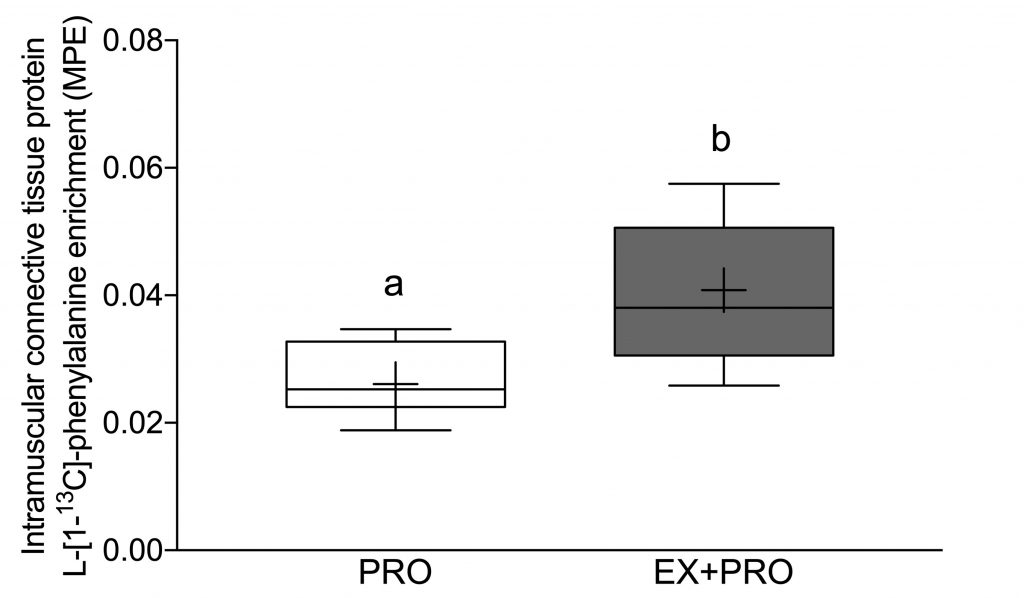

However, by building a tracer into our protein, we were able to see that our protein was built into the muscle connective tissue protein. This gives some hope that it may be possible to modulate connective tissue with nutritional interventions.

There are some possible explanations of why we did not observe an effect of protein ingestion.

First, it’s possible that the 30 g dose is not enough. Our previous research suggests you need at least 40 g pre-sleep protein to observe a clear effect on overnight myofibril protein synthesis (Trommelen, 2017), (Trommelen, 2016), (Snijders, 2019). The same might be true for muscle connective tissue protein synthesis. Because the overnight period is long, you might need more protein to get a clear effect over that period.

But keep in mind that the only study that observed a possible effect did so with 18 g of protein over a 5 h period. We measured 50% longer, but also gave >50% more protein.

Another possible explanation is that most protein sources do not have the right amino acid composition to stimulate muscle connective protein synthesis. The casein protein did not result in an increase in plasma glycine, one of the main amino acids in connective tissue. Perhaps a protein sources that better matches the composition of connective tissue protein (e.g. gelatin of hydrolyzed collagen) could be more effective?

And the final explanation is that protein may simply have no effect on muscle connective tissue protein synthesis. Almost all studies seem to support this, with only one study finding a possible effect with no clear explanation why (perhaps it was just coincidence?)

Our OPEN-ACCESS study:

Trommelen et al. Casein Ingestion Does Not Increase Muscle Connective Tissue Protein Synthesis Rates. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 2020

Hello Jorn, is my impression correct that connective tissue seems to be the bottleneck for most athletes? (as opposed to contractile tissue). does this effect get worse as athletes age?

Do you suggest taking a BCAA supplement before, during or after strength/resistance training? I feel like, for some reason, BCAA intake during exercise, since they would be freely available. Would lead to them getting oxidized and not actually simulating MPS. What do you think?

Thanks!

Nope, I see no scenario in which BCAA supplementation is the preferred option.

To stimulate MPS, you need all the essential amino acids in sufficient quantity. If not sufficient of the other EAA are present, then you would oxidize the BCAA (regardless of exercise).

Amino acids are not the preferred substrate during exercise. So if you ingested free amino acids, you wouldn’t necessarily oxidize them during exercise. Your body would use other substrates.

I have been seeing a lot of attention around collagen supplements lately. I never thought it was worth persueing as most “joint support” supplements add in 40mg of UCII collagen claiming it to be the clinical dose.

Maybe it would be worthwile to look into these “20g of collagen protein” kind of shakes to add to the pre-sleep supplementation. After all, connective tissue repair is just as important as contractile tissue growth. Maybe it could help prevent or heal tendon injuries which are the majority (in my case anyway).

There do seem to be specific types thought so not sure which might be best and why, if there is any difference at all to begin with. I’ve seen bovine based, marine based, chicken based,…

Your articles always get me rethinking what i (thought) i knew, great stuff!

regards,

Sven

Thank you Seven,

Yeah I don’t see collagen in the mg dose range doing anything.

But at doses in the gram range, perhaps there could be something to it.

If collagen supplementation turns to be effective, I would not expect much difference between the different sources (bovine, chicken etc..). In the end, it just has to provide the right amino acid precursors and they would all be suitable for that. It has been suggested that collagen might also have unique bioactive peptides (which could differ between sources), but I’m highly sceptical there’s anything to that.

I’d love to see protein vs collagen vs glycine.

Yep, me too.

In the perfect word, also:

– a high-dose protein matched for glycine and/or proline treatment

– vitamin C co-ingestion treatments