Studies are typically relatively short (weeks to months). However, we often want to know what happens with longer-term adherence to interventions such as a training protocol or a diet.

Therefore, data from studies needs to be extrapolated; make assumptions what would happen if the interventions would be continued.

Extrapolation requires assumptions. Essentially, we’re trying to make an educated guess what would happen. This guess should be based on the available data and logic.

For example, if a study observes 5 kg fat loss after 12 weeks on a diet, that does not necessarily mean you can expect an additional 5 kg fat loss in the next 12 weeks.

It is important to realize that extrapolation is heavily influenced by personal bias.

For example, if you are a proponent of a certain training style or diet, it is more likely that your extrapolation is (too) optimistic.

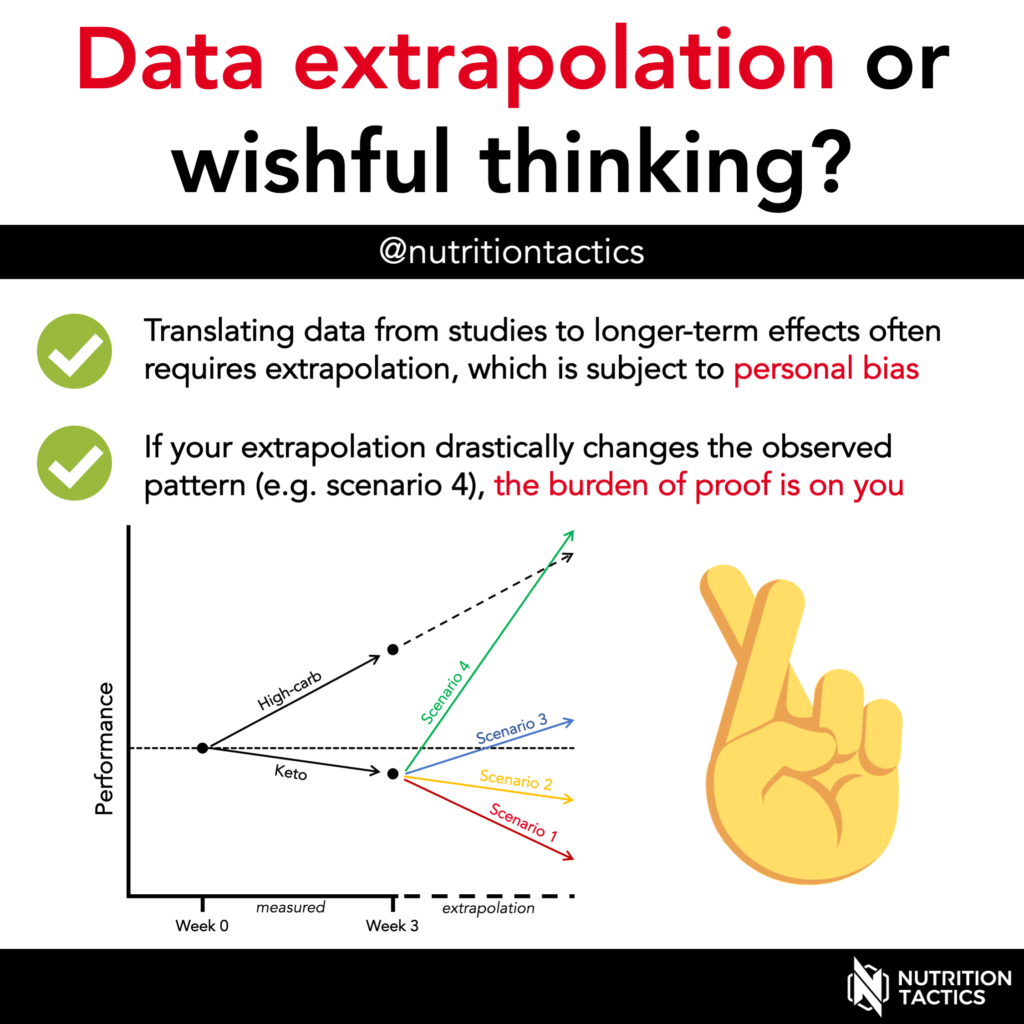

It has been shown that a ketogenic diet decreases exercise performance, while a high carbohydrate diet increases exercise performance during a 3-week training program.

A common critique is that this study gives a misleading picture, because the ketogenic diet is claimed to require a longer adaptation phase. Once the athlete is fully keto-adapted, the superiority of the ketogenic diet would become apparent (scenario 4).

But scenario 4 is a drastic change compared to the observed data, requires several assumptions, and therefore the burden of proof would be on those would claim this scenario is most likely.

An assumption of this scenario is that keto-adaptation requires >3 weeks, but there is no convincing supporting evidence.

The second assumption of this scenario is that further keto-adaptation would drastically improve exercise performance. However, it could also be argued that further keto-adaptation would only further decreases exercise efficiency and performance (scenario 1).

Leave a Reply