Muscle protein synthesis is the process of building muscle mass.

Muscle protein synthesis is essential for exercise recovery and adaptation. As such, it’s a really popular topic in the fitness community.

But the methods used to measure muscle protein synthesis in studies are very complicated. Some basic knowledge of the various methods is essential to draw proper conclusions from the research you’ll read.

The purpose of this article is to provide a comprehensive guide on muscle protein synthesis: what is it, how is it measured, what are the strengths and limitations, how to draw proper conclusions from muscle protein synthesis research, and of course practical guidelines how to optimize it.

I’ve made a table of contents, so you can jump to specific sections of interest or reference a specific section.

Please note that section 3 described the various methods to measure muscle protein synthesis. You might want to skip this section if you just want exercise and nutrition guidelines to optimize gains. Perhaps you can come back to it later when you are ready to become a true muscle protein synthesis research master.

I’ll be covering:

Contents

- 1. What is protein synthesis?

- 2. Why muscle protein breakdown is of less importance

- 3. Methods to measure protein synthesis

- 4. Interpretation and misconceptions

- 5. Advantages of muscle protein synthesis measurements over muscle mass measurements.

- 6. How to optimize muscle protein synthesis: exercise guidelines.

- 7. How to optimize muscle protein synthesis: nutrition guidelines

- 8. Summary

1. What is protein synthesis?

Protein is the main building block of your muscle.

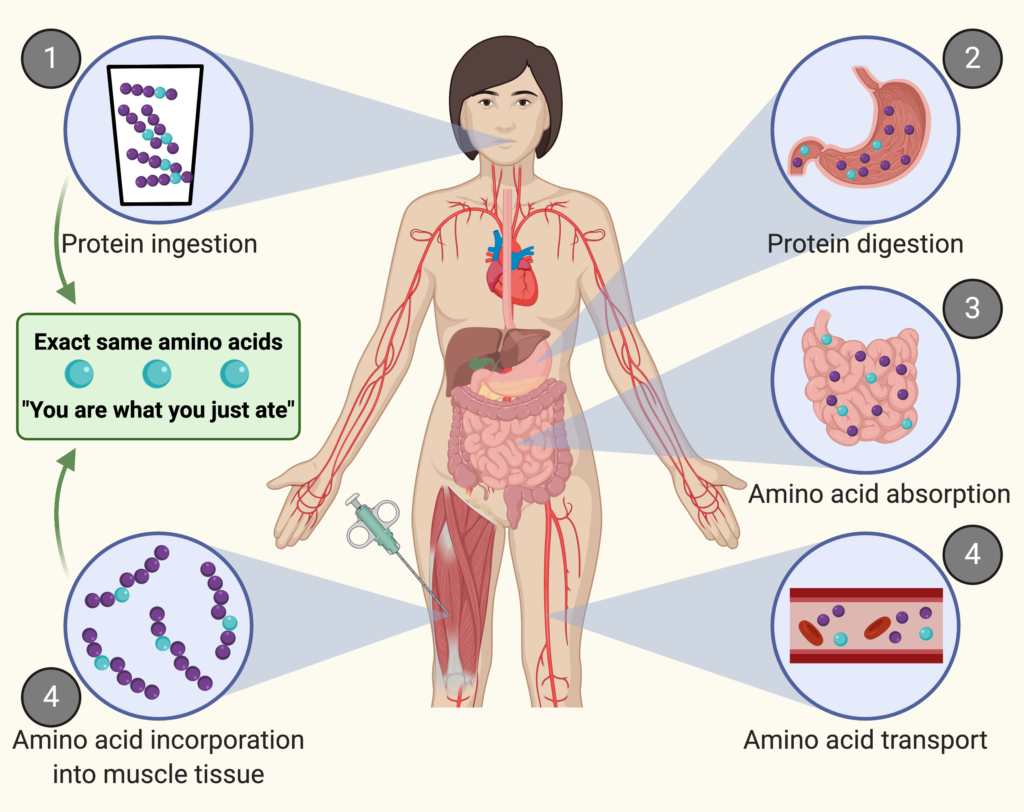

When you ingest protein, the protein is digested into amino acids. These amino acids are absorbed in the gut and subsequently released into the circulation. From there, the amino acids are transported to peripheral tissues where they are taken up and can be build into tissue protein.

Protein synthesis is the process of building new proteins. This process happens in all organs. Muscle protein synthesis is the process of building specifically muscle protein.

Think of a muscle as a wall. Each brick is an amino acid. Muscle protein synthesis is the addition of new bricks to the wall.

Now, this would mean the wall would become larger and larger. However, there is an opposing process. On the other side of the wall, a process called muscle protein breakdown is removing bricks. Muscle protein breakdown is also commonly referred to as muscle proteolysis or muscle degradation.

It’s important to realize that both muscle protein synthesis and breakdown are always ongoing. They are not “on” or “off”, but their speed can increase or decrease. The difference in speed of these two opposing processes determines the net change in muscle protein size.

If muscle protein in synthesis exceeds muscle protein breakdown, the wall will become larger (your muscles are growing). If muscle protein breakdown exceeds muscle protein synthesis, the wall is shrinking (you’re losing muscle mass).

The sum of these two processes determines your net balance:

net muscle protein balance = muscle protein synthesis – muscle protein breakdown.

You can also compare it to your bank account.

balance = income – expenses

2. Why muscle protein breakdown is of less importance

We’ll almost exclusively talk about muscle protein synthesis, and not focus much on muscle protein breakdown.

That might sound like you’re missing out on a whole lot, but you’re not.

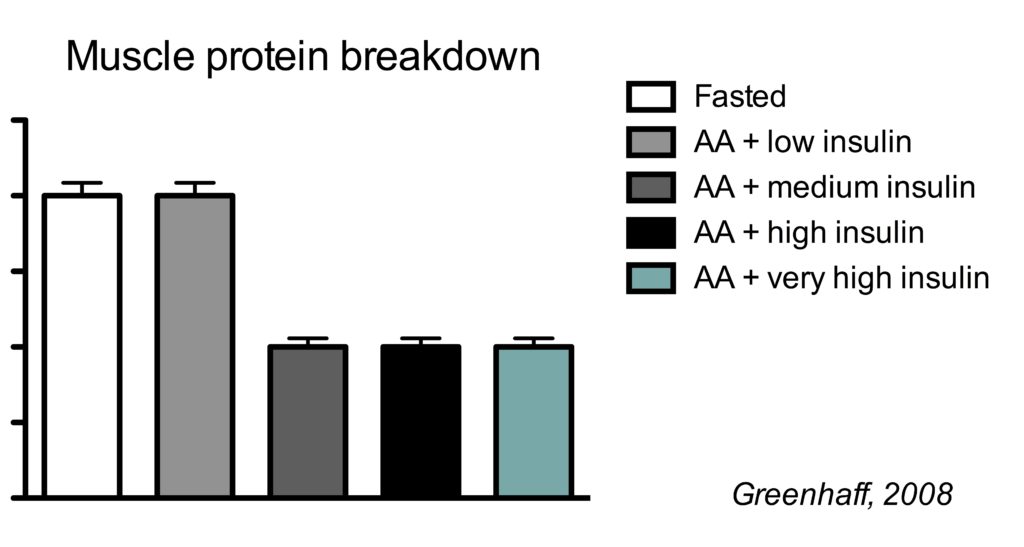

Changes in muscle protein synthesis are much greater in response to exercise and feeding than changes in muscle protein breakdown in healthy humans (Phillips, 1997)(Greenhaff, 2008).

While feeding can reduce muscle protein breakdown by approximately 50%, very little is needed to reach this maximal inhibition.

This is best illustrated by a study which clamped (maintained) insulin at different concentrations and also clamped amino acids at a high concentration.

There were five conditions:

- Fasted state

- high amino acids + low insulin

- high amino acids + medium insulin

- high amino acids + high high insulin

- high amino acids + very high insulin

In the illustration below, you see the effects on muscle protein breakdown.

In a fasted state, muscle protein breakdown rates were relatively high (condition 1). Amino acid infusion did not reduce muscle protein breakdown when insulin was kept low (condition 2). But when insulin was infused to reach a moderate concentration, muscle protein breakdown rates went down (condition 3). Further increasing insulin did not have an additional effect on muscle protein breakdown (conditions 4 and 5).

So this study shows us a couple of things.

Firstly, insulin inhibits muscle protein breakdown, but you only need a moderate insulin concentration to reach the maximal effect. In this study the medium insulin concentration already resulted in the maximal 50% muscle protein breakdown, but other research has shown that even half the insulin concentration of the medium group is already enough for the maximal effect (Wilkes, 2009).

Secondly, protein ingestion does not directly inhibit muscle protein breakdown. While protein intake can decrease muscle protein breakdown (Groen, 2015), this is because it increases the insulin concentration.

You only need a minimal amount of food to reach insulin concentrations that maximally inhibit muscle protein breakdown. In agreement, adding carbohydrates to 30 g of protein does not further decrease muscle protein breakdown rates (Staples, 2011).

Therefore, it often doesn’t make much sense to measure muscle protein breakdown in nutrition studies. All study groups that got at least some amount of food will have the 50% inhibition of fasted muscle protein breakdown rates. If the effect on muscle protein breakdown is the same between groups, then changes in muscle protein net balance would be entirely be explained by differences in muscle protein synthesis.

It should be noted that HMB decreases muscle protein breakdown in an insulin independent way (Wilkinson, 2013). It is not known of the effects of HMB and insulin on muscle protein breakdown are synergistic. However, HMB supplementation appears to have minimal effects of muscle mass gains in long-term studies (Rowlands, 2009).

Of course, you can speculate that muscle protein breakdown becomes more relevant during catabolic conditions during which there is significant muscle loss, such as dieting or muscle disuse (e.g. bed rest or immobilization). However, it cannot be simply assumed that the observed muscle loss in such condition is the result of increased muscle protein breakdown. After just 3 days of dieting, there is already a large decrease in muscle protein synthesis. In agreement, there is a large decrease in muscle protein synthesis during muscle disuse. Therefore, muscle loss may be largely (or even entirely) caused by a reduction in muscle protein synthesis, and not by an increase in muscle protein breakdown.

But let’s say that muscle protein breakdown does go up a bit during catabolic conditions. Then the first question would be, could nutrition prevent this? If the answer is no, muscle protein breakdown is still not that relevant to measure. If nutrition does have an effect, how much would it take? Let’s say you need double the amount of insulin you normally need to maximally inhibit muscle protein breakdown. That would still be a small amount of insulin that any small meal would release and all nutritional interventions have the same effect. So even during catabolic conditions, muscle protein synthesis rates are likely much more relevant than muscle protein breakdown.

While it sounds that muscle protein breakdown is a bad thing and we should try to completely prevent it, that is not necessarily true. Muscle proteins get damaged from exercise, physical activity, and metabolism (e.g. oxidative stress, inflammation etc). Muscle protein breakdown allows you to break down those damaged muscle proteins into amino acids and recycle most of them into new functional muscle proteins again.

In fact, muscle protein breakdown has beneficial roles in muscle growth and adaptation! If mice are genetically engineered so that they can’t properly break down muscle protein, they are actually weaker and smaller than normal mouses. This highlights that at least some amount of muscle protein breakdown is necessary to optimally adapt to training and maximize muscle growth (Bell, 2016).

So anytime you eat just about anything, you’ll reduce muscle protein breakdown by 50%. We don’t know how to reduce muscle protein breakdown even further, but it’s not clear if we would even want that, as at least some muscle protein breakdown seems necessary for optimal muscle growth.

3. Methods to measure protein synthesis

3.1 Nitrogen balance

Carbohydrates and fats are made of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen. In contrast, protein also contains nitrogen. So the nitrogen that we get through our diet has to come from protein.

As protein is broken down by the body, most of the protein derived nitrogen has to be excreted in the urine or it would accumulate and become toxic.

It’s fairly easy to measure nitrogen in food, feces, and urine. By doing so, we can calculate a balance:

nitrogen balance = nitrogen intake – nitrogen excretion

If nitrogen intake is bigger than nitrogen excretion, we are in a positive nitrogen balance. This indicates that your body stores more protein than it’s losing. This gives a general view that the body is in an anabolic (growing) state.

However, this method gives us very little insight into what exactly is going on.

You can have a positive nitrogen balance, while you’re losing muscle tissue. For example, your body might be building gut protein at a rate that exceeds your muscle loss.

As such, nitrogen balance is not that informative for athletes.

Example paper nitrogen balance: (Freeman, 1975)

3.2 Tracers

Before we go on to the next method, I need to introduce a new concept: tracers.

Tracers are compounds that you can trace throughout the body. Amino acid tracers are the most common type of tracers to assess muscle protein synthesis. These are amino acids that have an additional neutron. These amino acid tracers function identically to normal amino acids. However, they weigh slightly more than a normal amino acid, which allows us to distinguish them from normal amino acids.

A normal carbon atom has a molecular weight of 12. When we add a neutron, it has a weight of 13. We indicate these special carbons like this: L-[1-13C]-leucine. This means the amino acid leucine, has a carbon atom with a weight of 13. When you see such a notation in a paper, you know they’re using tracers.

Because you can follow amino acid tracers throughout the body, it allows us to measure various metabolic processes that happen to the amino acids, including protein synthesis.

3.3 Whole-body protein metabolism

Using amino acid tracers, we can measure protein synthesis, breakdown, oxidation and net balance.

Note that protein synthesis refers to protein synthesis of any protein in the body (whole-body protein synthesis). Again, do not mistake it for muscle protein synthesis, which is protein synthesis specifically of muscle protein. Therefore, (whole-body) protein synthesis measurements are not necessarily relevant for athletes and might actually give you the wrong impression (as will be discussed in chapter 3).

However, whole-body protein metabolism data provides more insight than the nitrogen balance method.

Nitrogen balance only indicates an overall anabolic or catabolic state. The whole-body protein metabolism method also indicated this by a positive or negative protein net balance. However, it also shows whether changes in net balance are because of an increase in protein synthesis, a decrease in protein breakdown, or a combination of both.

Please note that this does not contradict the earlier discussion on muscle protein breakdown is not that important. While muscle protein breakdown doesn’t change much, protein breakdown of other tissues can change drastically.

Instinctually, you might think that a more positive whole-body protein balance must be a good thing. However, that’s not really the case. It could simply mean that you’re building more gut protein, which is not something you would necessary want unless you want to have a bloated stomach.

Example paper whole-body protein metabolism: (Borie, 1997)

3.4 Two pool and three pool arteriovenous technique

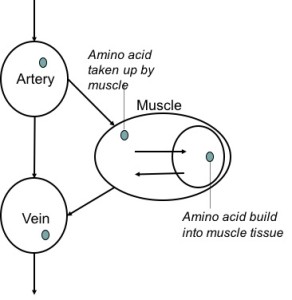

These methods measure amino acid concentrations in the artery to a muscle, and the vein from that muscle.

Let’s say that the amino acid concentration is low in the artery going to a muscle and high in the vein coming from that muscle. Where did those extra amino acids in the vein come from? They’re released from the muscle, and it would indicate that the muscle is breaking down. Conversely, if the muscle would take up a lot of amino acids from the artery, but releases less amino acids to the vein, it would indicate that the muscle is taking up a lot of amino acids to build muscle proteins.

This method is called the two pool arteriovenous method. A drawback of this method is that you don’t really know for sure what is going on in the muscle. Just because a muscle is taking up amino acids, that does not mean it’s building all of those amino acids into actual muscle tissue.

To solve this problem, this method can be combined with muscle biopsies. This is called the three pool model and allows us to see what happens to the amino acids once they’re taken up by the muscle.

The main advantage of this method is that it measures both muscle protein synthesis and muscle protein breakdown. However, the calculations are depended on blood flow measurements, which we can’t measure all that accurately. Therefore, this is not the preferred method for measuring muscle protein synthesis.

Example paper 3 pool model: (Rasmussen, 2000)

3.5 Fractional synthetic rate

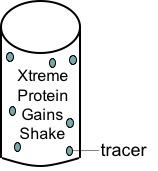

This method combines the infusion of amino acid tracers with muscle biopsies.

The most basic explanation is that you take a pre and post muscle biopsy, and measure the rate at which the amino acid tracer is built into the muscle.

This method gives you a fractional synthetic rate (FSR), expressed as %/h. It shows you how fast a muscle would rebuild itself entirely. An FSR of 0.04 %/h means that each hour, 0.04% of the total muscle is synthesized. This translates to a completely new muscle every 3 months. To regenerate as fast as Wolverine of the X-men, you would need an FSR of 100000 %/h in all your tissues.

This is the most common method of measuring muscle protein synthesis.

A minor drawback of this method is that it requires a ”steady state” to have the most accurate measurements. I don’t want to go into too many details, but it often means plasma amino acid enrichment should stay at the same level (the ratio of the tracer amino acid to the normal amino acid). However, protein ingestion would disturb this steady state, as a lot of normal amino acids will enter the blood, thus throwing off the tracer amino acid to normal amino acid ratio. Therefore, a lot of older studies provided protein in small sips, which wouldn’t disturb the steady state.

A slight disturbed steady state isn’t the end of the world for the measurement, but it’s sometimes something to consider when evaluating the data.

However, our lab has gotten fancy in this area. We have been able to produce highly enriched intrinsically labeled protein. This means that the amino acid tracers have been build into our protein supplements. So as our intrinsically protein supplements are absorbed, both amino acid tracers and normal amino acids enter the blood. Therefore the steady state is not disrupted and FSR can be calculated more accurately.

Example paper FSR (with and without intrinsically labeled protein): (Holwerda, 2016)

3.6 De novo muscle protein synthesis

The highly enriched intrinsically labeled protein has another advantage.

You can trace the amino acids from the protein: first, as they are digested, then as they appear in the blood, subsequently they are taken up by the muscle, and ultimately some of them are built into actual muscle tissue. So we can measure how much of the protein you eat, actually ends up into muscle tissue.

This is called de novo muscle protein synthesis. It’s building new muscle protein from your food, in contrast to building muscle protein by recycling amino acids from protein breakdown.

Example paper de novo muscle protein synthesis: (Trommelen, 2017).

3.7 Specific muscle protein fractions

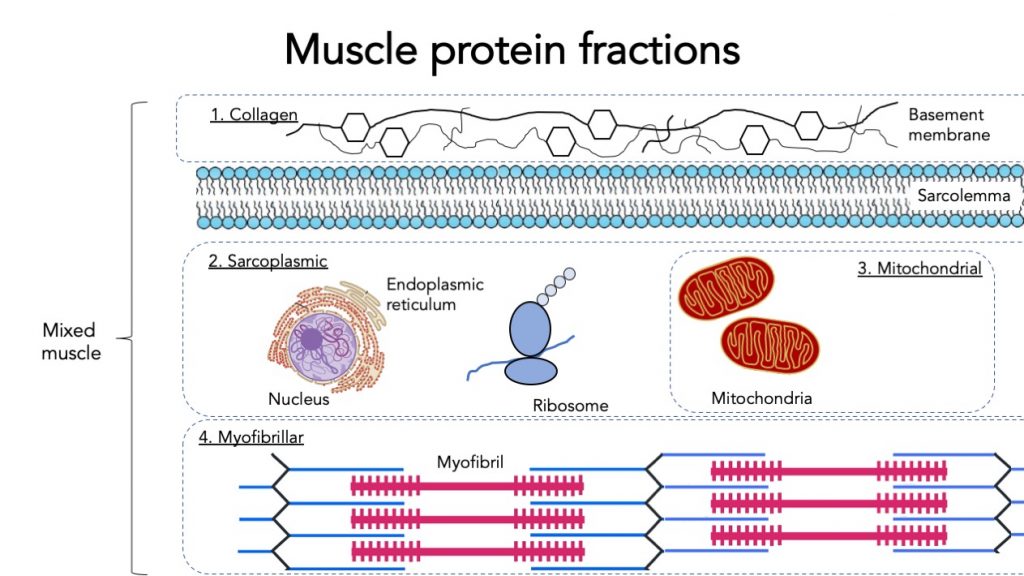

When measuring muscle protein synthesis, we can measure mixed muscle protein synthesis (all types of muscle protein together). But muscle protein can be further specified into fractions.

The main muscle protein fraction is myofibrillar protein. Myofibrillar proteins contract and represent the majority of the muscle mass. This fraction is highly relevant for building muscle mass and strength.

Mitochondrial proteins only represent a small part of the muscle. Mitochondria are the powerhouses of the muscle, they burn carbohydrate and fat for fuel. Therefore mitochondrial protein synthesis is more informative about energy production capacity in the muscle and more relevant for endurance athletes and metabolic health.

Sarcoplasmic protein contains various organelles such as the endoplasmic reticulum and ribosomes.

Intramuscular connective tissue protein represents collagen protein in the muscle. This collagen helps transfer the muscle force generated by myofibrillar protein. It may be relevant for strength, injury prevention, and mobility, but we don’t know that much about it yet.

Example paper myofibrillar vs mitochondrial protein synthesis: (Wilkinson, 2000), or intramuscular connective tissue protein synthesis (Trommelen, 2020)

- Mixed muscle protein synthesis measures the synthesis of all muscle proteins.

- Myofibrillar protein synthesis measures only contractile proteins and is the most relevant measurement for muscle mass gains.

- Mitochondrial protein synthesis is more relevant for endurance and metabolic health.

3.8 Deuterium oxide

More recently, deuterium oxide (D2O, also called heavy water) is getting popular to measure muscle protein synthesis.

I’m going to skip most of the technical details, but the big difference with amino acid tracers is that this technique can accurately measure muscle protein synthesis days or even weeks, whereas the amino acid tracer technique measures muscle protein synthesis accurately over hours. In the next section, we’ll explain why this matters.

Example paper deuterium oxide: (Brooks, 2015)

3.9 Molecular markers

There is evidence that a variety of signaling molecules are involved in the regulation of muscle protein synthesis. Most notably, the protein from the mTOR pathway. Research of these molecular markers is very important to better understand how physiological processes are regulated and ultimately can be influenced by exercise, nutrition or even drugs.

However, at this point, we don’t understand them well for them to be useful predictors of physiology. In other words, while mTOR activation is involved in the regulation of muscle protein synthesis, an increase in mTOR activation doesn’t necessarily mean that muscle protein synthesis will actually increase.

Therefore, you should be very skeptical to draw conclusions based on studies that only measure molecular markers of muscle protein synthesis and muscle protein breakdown.

Example paper molecular markers (in this paper they don’t reflect actual MPS measurements): (Greenhaff, 2008)

4. Interpretation and misconceptions

Methods are not necessarily good or bad. But the interpretation of the data based on these methods can be wrong.

4.1 Whole-body protein synthesis vs muscle protein synthesis

We recently showed that resistance exercise does not increase whole-body protein synthesis (Holwerda, 2016). So should we conclude that resistance exercise is not effective to build muscle?

Absolutely not.

Whole-body protein metabolism measures the synthesis of all proteins in the body. Resistance exercise specifically builds muscle protein; it doesn’t increase protein synthesis in other organs. Other tissues in the body have much higher synthesis rates, and therefore, the muscle only has a relatively small contribution to the total whole-body protein synthesis rates. Therefore, you don’t see an increase in whole-body protein synthesis following resistance exercise.

In the same study, we also measured muscle protein synthesis (using the FSR method both with and without intrinsically labeled protein) and de novo muscle protein synthesis. All 3 methods showed that resistance exercise was anabolic for the muscle.

So resistance exercise did exactly what it’s supposed to do: build muscle, not build your other organs.

Often, labs don’t have the money or expertise to do many of these measurements. Imagine we would have only measured whole-body protein synthesis. Our study would give the wrong impression that resistance exercise is not anabolic, as we saw no increase in whole-body protein synthesis rates. Therefore it’s important that you understand the difference between whole-body protein synthesis and muscle protein synthesis methods.

Let’s discuss another example:

This study has been getting a lot of attention:

”The anabolic response to a meal containing different amounts of protein is not limited by the maximal stimulation of protein synthesis in healthy young adults” (Kim, 2016).

Shortly, it says that very large protein meals are beneficial because they reduce protein breakdown.

This gathered a lot of attention on social media and some of the comments were:

– See we shouldn’t ignore muscle protein breakdown!

– See that you need more than 40 gram of protein in each meal!

Again, this study gave the wrong impression, because whole-body protein breakdown was mistaken for muscle protein breakdown (the latter was not measured in this study). In case you’re wondering, this study did measure muscle protein synthesis. Both the 40 gram and the 70 gram dose were equally effective at stimulating muscle protein synthesis. So this study doesn’t indicate that you need more than 40 gram of protein each meal as an athlete.

4.2 Correlation muscle protein synthesis and muscle mass gains

One of the purposes of measuring muscle protein synthesis is to study if an intervention helps to build muscle or maintain muscle mass.

On social media, I occasionally see people dismissing muscle protein synthesis studies by claiming:

”it’s just an acute mechanistic study, it doesn’t necessarily translate to long-term changes in muscle mass”.

While there is some truth to the statement, it’s massively overused and often used as a cop-out as they have limited understanding of muscle protein synthesis. In fact, there are strong benefits for acute muscle protein synthesis studies over long-term training studies, which I’ll discuss in the next section.

Let me first get something out of the way: we have no bias for either acute or long-term studies. We run both at our lab, and do some of the most expensive studies in the field of either type.

The concern that muscle protein synthesis may not translate to muscle mass gains got an uprise when the following study was published:

”Acute post-exercise myofibrillar protein synthesis is not correlated with resistance training-induced muscle hypertrophy in young men” (Mitchell, 2014).

A lot of people seem to think that based on this study, muscle protein synthesis measurements do not translate to actual muscle mass gains in the long term.

But that conclusion is way beyond the context of the study. This study measured muscle protein synthesis in the 6 hours after a single exercise bout. However, resistance exercise can increase muscle protein synthesis for several days. So a 6-hour measurement does not capture the entire exercise response. This study showed that measuring muscle protein synthesis for 6 hours does not predict muscle mass gains. That is totally different from the conclusion that muscle protein synthesis (regardless of measurement time) does not predict muscle mass gains.

This was followed up by a study which used the deuterium oxide method to measure muscle protein synthesis rates during all the weeks of training (not just a few hours after one session), and found that muscle protein synthesis did correlate with muscle mass gains during the training program (Brooks, 2015).

More recently, a study found that muscle protein synthesis measured over 48 hours after an exercise bout did not correlate with muscle mass gains in untrained subjects at the beginning of an exercise training program, but it did at three weeks of training and onwards (Damas, 2016). While untrained subjects have a large increase in muscle protein synthesis after their initial exercise sessions, they also have a lot of muscle damage. So muscle protein synthesis is mainly used to repair damaged muscle protein, not to grow. After just 3 weeks of training, muscle damage is diminished, and the increase in muscle protein synthesis is actually used to hypertrophy muscles.

So do these studies show that muscle protein synthesis predicts muscle mass gains, but only in the right context.

- Exercise elevates muscle protein synthesis for 24 hour or longer: ideally you have a muscle protein measurement of 24 hours or longer and have ‘trained’ subjects so training induced muscle damage is attenuated (3 weeks of training is enough)

- Protein ingestion increased muscle protein synthesis for ±3-6 hours, so ideally you have measurement period of 6 hours (longer would actually be detrimental)

5. Advantages of muscle protein synthesis measurements over muscle mass measurements.

A huge benefit of muscle protein synthesis studies is that they are more sensitive than studies that measure actual muscle mass gains. This means that muscle protein synthesis studies can detect an anabolic effect easier than long term studies which simply miss it (long term studies might draw the wrong conclusion that something does not benefit muscle growth when it actually does).

For example, it has been shown time and time again that protein ingestion increases muscle protein synthesis. But the vast majority of long-term protein supplementation studies (80%) have found that protein supplementation does not increase muscle mass gains (Cermak, 2012).

This is because most long term studies are underpowered, aka don’t have enough statistical power to find small positive effects. Muscle mass gain is simply a very slow process. You need to do a huge study, with a huge amount of subjects, who consume additional protein for many months, before you will actually see a measurable effect of protein supplementation.

We performed a meta-analysis (combining the results of individual studies) on the effect of protein supplementation on muscle mass gains. We demonstrated that only 5 studies concluded that protein supplementation had a benefit, while 17 did not! However, most of the studies that showed no significant benefit, did show a small (non-significant) benefit. When you combine all those results, you increase the statistical power and you can conclude that protein supplementation actually does improve muscle mass. So in this case, most long-term studies gave the wrong impression, and muscle protein synthesis studies are actually preferred.

There are a lot of long-term studies that have a relative small number of subjects and a small study duration and conclude that an intervention did not work (for example, protein supplementation, or X versus Y set of exercise for example). However, the studies were doomed to begin with. They needed to be 3 times as big and 2 times as long to have a chance to find a positive effect. These studies unfortunately give people the impression that something doesn’t work, while it actually might/does.

Now if the effect of giving additional protein is already extremely hard to detect in long-term studies, how realistic is it to find smaller effects? For example, optimizing protein intake distribution throughout the day has been shown to optimize muscle protein synthesis rates (Mamerow, 2014)(Areta, 2013). However, this effect is smaller than adding another protein meal. So the effect of protein distribution is almost impossible to find in a long-term study. For such a research question, acute muscle protein synthesis studies are simply much better suited.

The second big benefit of muscle protein synthesis studies is that they give a lot more mechanistic insight. They help you understand WHY a certain protein is good or not that good at stimulating muscle protein synthesis (for example, its digestion properties, amino acid composition etc). These kinds of insights help to better understand what triggers muscle growth and come up with new research questions. These kind of insights are very hard to obtain in long-term studies, which typically only show the end result of the mechanisms.

The benefits of measuring muscle protein synthesis include the sensitivity, controlled environment, and they allow you to investigate questions that are almost impossible to answer in long-term studies. In addition, they’ll give you a lot of mechanistic insight, which opens the door for future research.

But ultimately, it’s not a matter of which type of study is better. Again, we do both and each has its purpose and build on each other. Usually, muscle protein synthesis studies are performed to see if something work (as they are very sensitive) and why it works. Once we think we have a good understanding, then we’ll try to see if the concept has the expected effect in a long-term study. Only when you have both, you have pretty convincing evidence that your intervention does what you claim it to do.

6. How to optimize muscle protein synthesis: exercise guidelines.

Now it’s time to translate the muscle protein synthesis to some practical recommendations.

6. 1 Number of sets

Multiple sets increase muscle protein synthesis more than a single set (Burd, 2010). A higher weekly training volume (number of sets to muscle) results in a greater muscle mass gains (Schoenfeld, 2016).

6.2 Reps per set

It is often recommended that a rep range of 8-12 reps per set is optimal for muscle growth. The American College of Sport Medicine position stand states (ACSM, 2009):

For novice (untrained individuals with no RT experience or who have not trained for several years) training, it is recommended that loads correspond to a repetition range of an 8-12 repetition maximum (RM). For intermediate (individuals with approximately 6 months of consistent RT experience) to advanced (individuals with years of RT experience) training, it is recommended that individuals use a wider loading range from 1 to 12 RM in a periodized fashion with eventual emphasis on heavy loading (1-6 RM) using 3- to 5-min rest periods between sets

However, these recommendations lack evidence. More recently, Stu Phillip’s lab has performed a series of studies demonstrating that repetition load plays a minimal, if not negligible, role in the hypertrophic response to resistance exercise, if sets at the different rep ranges are performed to failure (Burd, 2010)(Morton, 2016).

The main takeaway here is that there are no magic rep ranges that are superior for muscle growth.

6.3 Training to failure

It is unclear whether each set should be taken to failure. Muscular failure decreases performance on subsequent sets, thereby reducing training volume. In addition, it has been suggested that frequent, high volume training with each set to taken to failure results in ‘overtraining’, eventually forcing reduced training volume or intensity for recovery (Stone, 1996).

Perhaps performing a set with 1-2 reps left in the tank will still give a near-maximal stimulus to the muscle, without much of the associated fatigue. If sets are not taken close to failure, the muscle protein synthetic response will be small (Burd, 2010). But at least in untrained subjects, training close to failure appears to produce similar muscle mass gains as training to complete failure (Nóbrega, 2017).

6.4 Rest between sets

A longer rest period between sets increases the larger post-exercise muscle protein synthetic response compared to a short rest period (5 vs 1 min)(McKendry, 2016). In agreement, a longer interset rest period improves muscle mass gains compared to a shorter rest period (3 vs 1 min) (Schoenfeld, 2016).

6.5 Training frequency

A single bout of resistance exercise can stimulate muscle protein synthesis for longer than 72 hour, but peaks at 24 h (Miller, 2005). This suggests that the popular so called ‘bro-split’ (hitting each muscle group once a week on different training days) is suboptimal. Indeed, training each muscle group at least twice a week results in larger muscle mass gains (Schoenfeld, 2016).

6.6 Training status

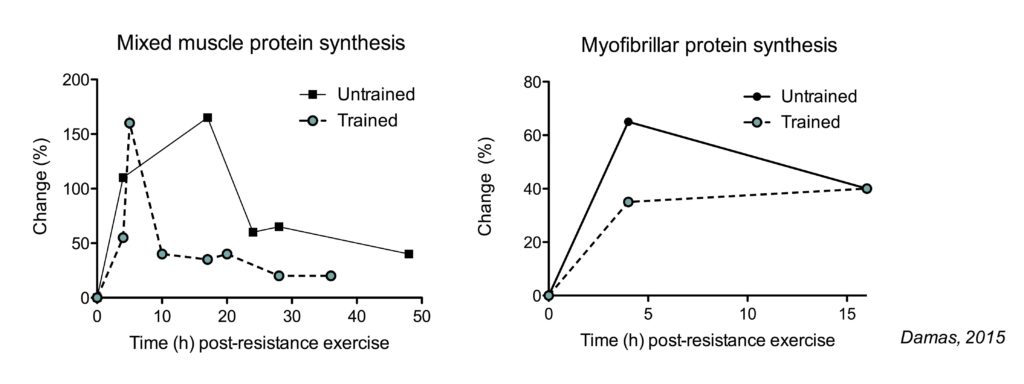

The total muscle protein synthetic (MPS) response (determined by the increase in MPS rates and the duration of these increased rates) is decreased in trained subjects compared to untrained subjects (Damas, 2015). However, the pattern of this decreased response is differs between mixed muscle protein synthesis (the synthesis of all types of muscle proteins) and myofibrillar protein synthesis (the synthesis of contractile proteins: the relevant measurement for muscle mass).

The increase in mixed muscle protein synthesis is shorter lived in trained subjects. In contrast, myofibrillar protein synthesis rates do not increase as much in trained subjects, but the duration of the increase does not appear impacted.

The larger increase in the total muscle protein synthetic response seems like a logical explanation why untrained people can make faster much gains than experienced lifters. However, this is not necessarily true.

In untrained subjects, there is not only a large increase myofibrillar protein synthesis, but also in muscle damage following resistance exercise. A large portion of the myofibrillar protein synthesis is used to simply repair damaged muscle proteins, rather than growing muscle proteins. In more trained subjects, here is a smaller increase in myofibrillar protein synthesis, but there is also much less or even minimal muscle damage following resistance exercise (just 3-10 weeks of training is enough to see these effects). This means that in a trained state, the increase in myofibrillar protein synthesis can actually be used to actually increase muscle mass. When you correct for muscle damage, myofibrillar protein synthesis rates measured over 48 hour post-exercise recovery are similair in untrained subjects and after 10 weeks of training (Damas, 2016).

Of course, most athletes would hardly consider someone trained after just 10 weeks. Unfortunately, little is know about how years of serious training impacts the muscle protein synthetic response to resistance exercise. While it’s tempting to speculate on how and if advanced athletes should modify training variables compared to untrained subjects, there is no solid evidence to support such suggestions.

7. How to optimize muscle protein synthesis: nutrition guidelines

7.1 Amount of protein

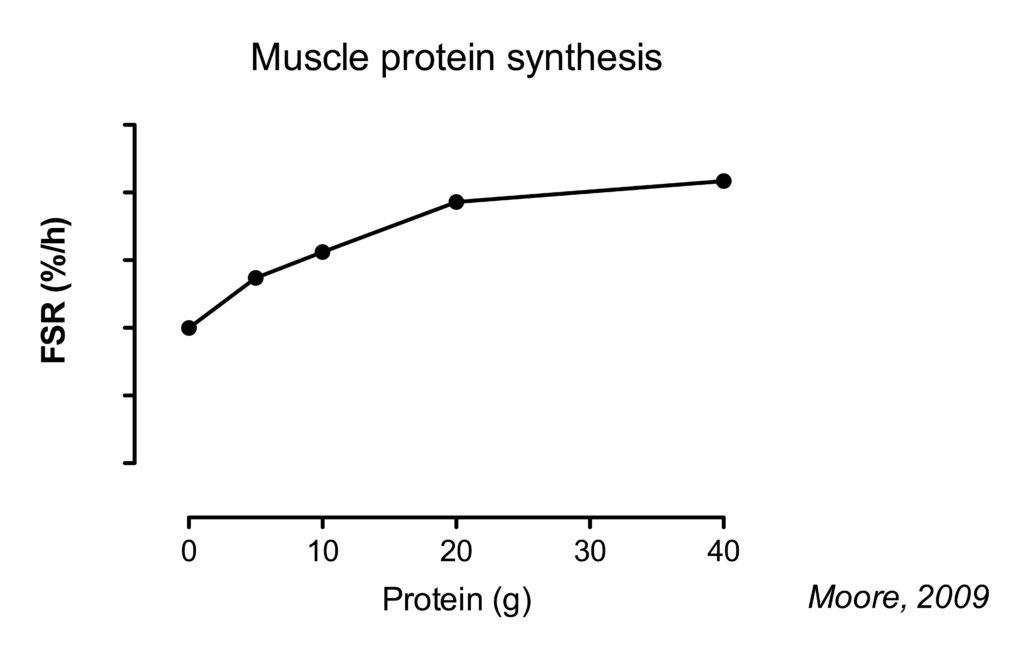

Twenty gram of protein gives a near-maximal increase in MPS after lower body resistance . Going up further to 40 g, results in a approximately 10% higher MPS rates (Moore, 2009)(Witard, 2014).

When data of several studies was combined and the amount of protein was expressed per bodyweight, it was found that on average 0.24 g/kg bodymass (or 0.25 g/kg lean body mass) would optimize muscle protein synthesis. However, the authors suggest a safety margin of 2 standard deviations to account for inter-intervidual variability, resulting in a dose of protein that would optimally stimulate MPS at an intake of 0.40 g/kg/meal (Moore, 2015).

More recently, it has been shown that the amount of lean body mass does not impact the response to protein ingestion (Macnaughton, 2016). In other words: bigger dudes don’t need more protein to get the same response as smaller guys.

However, this study found that 40 g of protein resulted in approximately 20% higher higher MPS rates compared to 20 g. The authors speculated that this was related to the fact that this was following a session of whole-body resistance exercise compared to the lower-body exercise used in previous studies.

7.2 Protein source

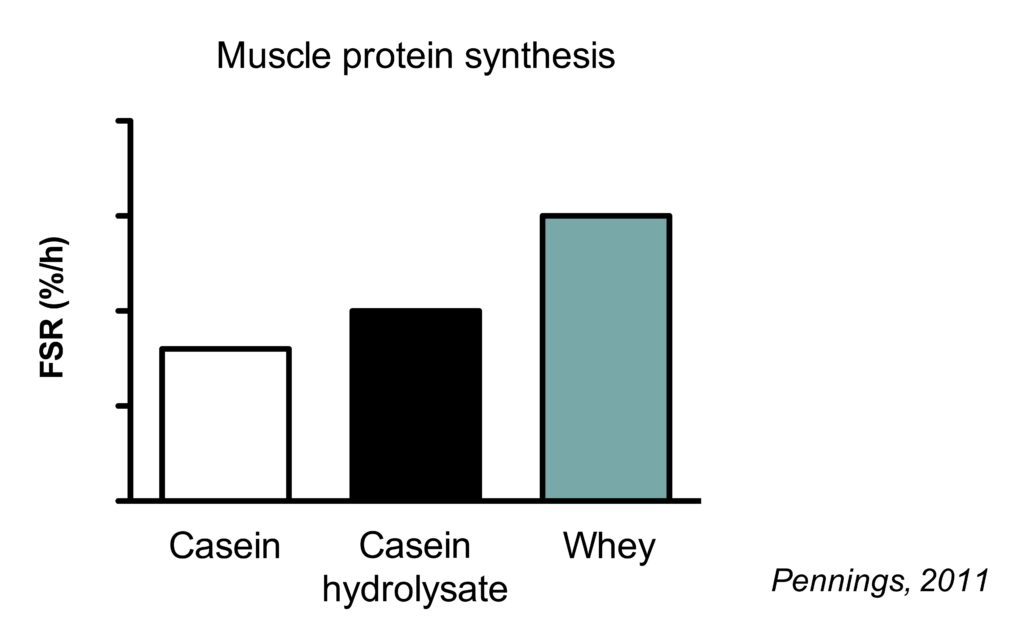

Protein sources differ in their capacity to stimulate MPS. The main properties that determine the anabolic effect of protein are it’s digestion rate and it’s amino acid composition (particularly leucine).

This is best illustrated by study which compared the muscle protein synthetic response to casein, casein hydrolysate and whey protein.

Casein is a slowly digesting protein. When intact casein is hydrolyzed (chemically cut into smaller pieces), it resembles the digestion of a fast-digesting protein. Consequently, hydrolyzed casein results in higher MPS rates than intact casein.

However, the muscle protein synthetic response to hydrolyzed is lower than that of whey protein. While both proteins are fast digesting, whey protein has a higher essential amino acid content (including leucine) (Pennings, 2011).

Animal based protein sources are typically have a high essential amino acid content and appears more potent than plant protein to stimulate MPS (Van Vliet, 2015). However, there this can potentially compensated by ingesting a greater amount of plant protein (Gorissen, 2016).

7.3 Leucine

Leucine is the amino acid that is thought to be most potent at stimulating MPS. Peak plasma leucine concentrations following protein ingestion typically correlate with muscle protein synthesis rates (Pennings, 2011). This supports the notion that protein digestion rate and protein leucine content are important predictors for anabolic effect of a protein source.

While leucine is very important, other amino acids also play a role,

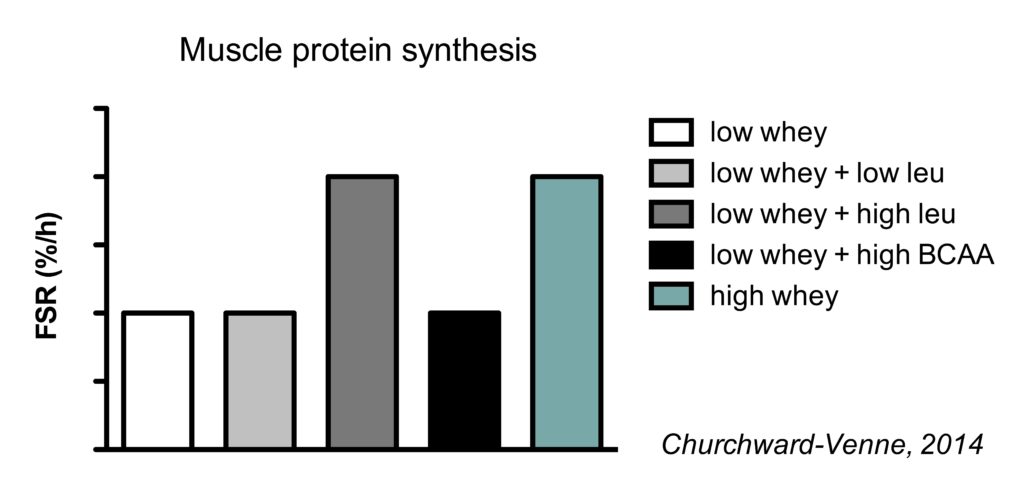

This is best illustrated by study (Churchward-Venne, 2014) which compared the muscle protein synthetic response to five different supplemental protocol:

- 6.25 g whey

- 6.25 g whey with 2.25 g leucine for a total of 3 g leucine

- 6.25 g whey with 4.25 g leucine added for a total of 5 g leucine

- 6.25 g whey with 6 g BCAA added (4.25 g leucine, 1.38 g isoluecine for, and 1.35 g valine)

- 25 g whey (contains a total of 3 g leucine)

All five conditions increased muscle protein synthesis rates compared to fasting conditions. As expected from our earlier discussion on the optimal amount of protein, 25 gram of protein increased MPS rates more than just 6.25 gram.

Interestingly, the addition of 2.25 gram leucine to 6.25 gram whey did not further improve MPS. Since this low whey + low leucine amount had the total amount of leucine as 25 g whey (which contains 3 g leucine), it indicates that leucine alone doesn’t determine the muscle protein synthesis response.

The addition of a larger amount of leucine (4.25 gram) to the 6.25 gram whey did further improve MPS, with MPS rates being similar to the 25 gram of whey. This indicates that the addition of a relatively small amount of leucine to a low dose of protein can be as effective as a much larger total amount of protein.

Finally, it’s really interesting that the addition of the 2 other branched-chain amino acids (BCAA) appeared to prevent the positive effect of leucine on MPS. Isoleucine and valine use the same transporter for uptake in the gut as leucine. Therefore, it is speculated that isoleucine and valine compete for uptake with leucine, resulting in a less rapid leucine peak which is thought to be an important determinant of MPS rates.

7.4 Carbohydrate or fat co-ingestion

Carbohydrates slows down protein digestion, but have no effect on MPS (Gorissen, 2014). In agreement, adding large amounts of carbohydrates to protein does not improve post-exercise MPS rates (Koopman, 2007).

In addition to the effects on protein digestion, it has been suggested that carbohydrates stimulate insulin release, which may stimulate muscle protein synthesis and/or muscle protein breakdown rates. However, the addition of carbohydrates to post-exercise protein has no effect on muscle protein synthesis or breakdown rates. The effects of insulin on muscle protein breakdown rates are described in more detail in section 2, and the effects of insulin on muscle protein synthesis are further described in section 7.6.

Adding oil to protein does not slow down protein digestion or MPS (Gorissen, 2015). It possible that oil simply floats on top of a protein shake in the stomach, and that a solid fat would delay digestion. One study has reported a greater increase in net muscle balance following full-fat milk compared to fat-free milk (although this study used the 2 pool arterio-venous model which is not the most reliable measurement).

7.5 Whole food and mixed meals

Most research has looked at isolated protein supplements in liquid form such as whey and casein shakes.

Thirty gram protein provided in the form of 113 gram 90% lean grounded beef results in a similar MPS response as 90 gram protein (340 gram beef). This supports the protein dose-response relationship observed with protein supplements where 20 g of protein gives a near maximal increase in MPS.

Minced beef is more rapidly digested than beef steak, indicating that food texture impacts protein digestion. However, there was no difference in MPS between these protein sources.

Beef protein is more rapidly digested than milk protein. However, milk protein stimulated MPS more than beef in the 2 hours (Burd, 2015). Between 2 and 5 hours, there was no significant difference between the sources. This indicates that digestion speed does not always predict the muscle protein synthetic response of a protein source.

As discussed in the previous section, the addition of carbohydrate powder or oil to a liquid protein shake does not impact muscle protein synthesis. However, it is unknown how the components of (large) mixed meals interact. For example, the addition whole-foods carbohydrates such rice, potatoes, or bread to whole-food protein sources such as chicken.

It can be speculated that the protein in mixed meals is less rapidly digested, which is typically (but not certainly not always) associated with a lower increase in MPS.

7.6 Insulin

As described in my systematic review, insulin does not stimulate MPS (Trommelen, 2015).

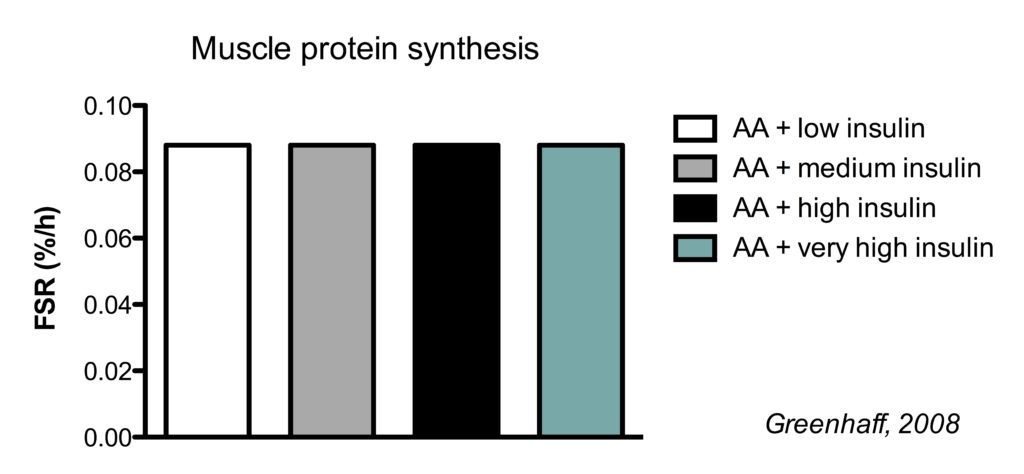

This is best illustrated by a study which clamped (maintained) insulin at different concentrations and also clamped amino acids at a high concentration.

There were four conditions:

- high amino acids + low insulin

- high amino acids + medium insulin

- high amino acids + high high insulin

- high amino acids + very high insulin

In the illustration below, you see the effects on muscle protein synthesis.

Regardless whether insulin levels were kept low (similar to fasted levels) or very high, MPS rates were the same in all conditions.

In my systematic review, I describe the effect of insulin in other conditions including in the absence of amino acid infusion, but the conclusion remains that insulin does not stimulate MPS under normal conditions (Trommelen, 2015). However, it should be noted that insulin stimulates MPS at at supraphysiological (above natural levels) doses (Hillier, 1998). In the bodybuilding world, insulin is sometimes injected at supraphysiological doses to stimulate muscle growth.

Insulin inhibits muscle protein breakdown a bit, but only a little is needed for the maximal effect (this is discussed in dept in section 2). A protein shake alone increases enough insulin to maximally inhibit muscle protein breakdown, you don’t need additional carbohydrates (Staples, 2011).

7.7 Protein timing

Exercise improves the muscle protein synthetic response to protein ingestion. Therefore, it has been suggested that protein intake immediately post-exercise is more anabolic than protein ingestion at different time points.

Probably the best evidence to support the concept of protein timing is a study which showed that protein ingestion immediately after exercise was more effective than protein ingestion 3 h post-exercise (though this study used the 2 pool arterio-venous method which is not a great measurement of muscle protein synthesis) (Levenhagen, 2001). In contrast, a different study observed no difference in MPS was found when essential amino acid were ingested 1 h or 3 h post-exercise (Rasmussen, 200).

In addition, resistance exercise enhances the muscle protein synthetic response to protein ingestion for at least 24 hour (Burd, 2011). It is certainly possible that the synergy between exercise and protein ingestion is the largest immediately post-exercise and then slowly declines in the next 24 h hour. However, these data suggest that there is not a limited window of opportunity during which protein is massively beneficial immediately post-exercise, that suddenly closes within a couple of hours.

Overal, no clear benefit to protein timing has been found in studies measuring muscle protein synthesis studies. As such studies are much more sensitive to detect potential anabolic effects compared to long-term studies measuring changes in muscle mass, it unlikely that long-term studies will observe benefits of protein timing.

In agreement, a meta-analysis concluded that protein supplementation ≤ 1 hour before and/or after resistance exercise improved muscle mass gains (Schoenfeld, 2013). However, this effect was largely explained by the fact that the protein supplementation increased total protein intake, rather than the specific timing of protein intake.

From a practical perspective, a protein shake during or after a workout:

- is easy to do

- theoretically may have a very small benefit

- is a simple method to improve total protein intake

- prevents FOMO (fear of missing out on something)

So it could be argued: why not do it? It is mostly up to personal preference.

7.8 Protein distribution

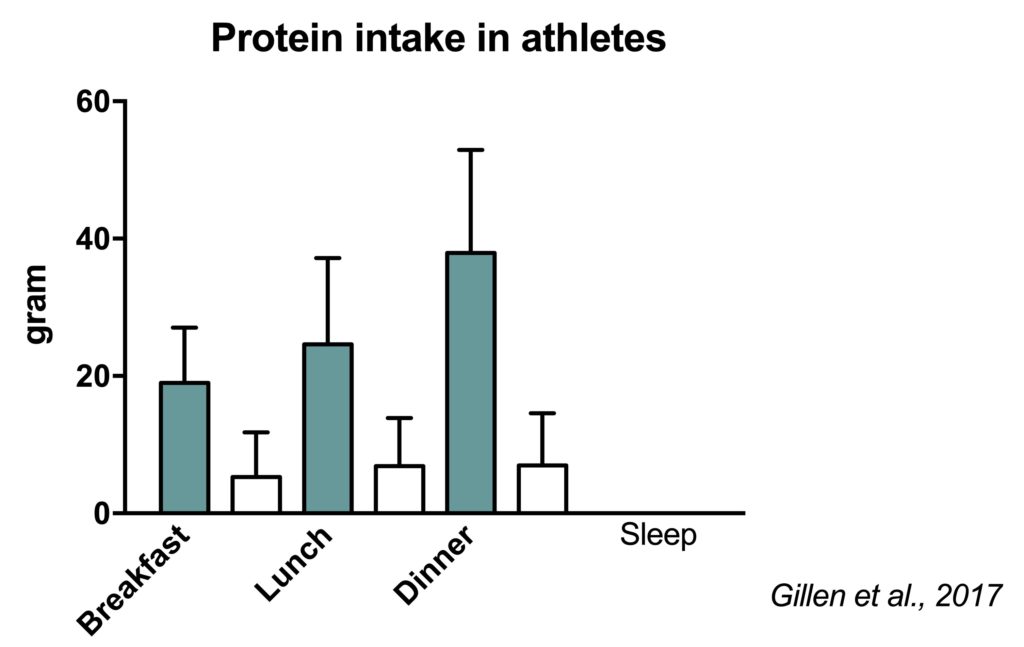

We performed a study to assess protein intake in well-trained Dutch athletes. Even some Olympic athletes were included. We observed that athletes consumed ~1.5 g protein/kg/d based on multiple dietary recalls (Gillen, 2017). However, their real protein intake is likely ~25% higher based on a nitrogen excretion validation study we performed in a subgroup (Wardenaar, 2015).

The majority of the protein was consumed in the three main meals: breakfast, lunch and dinner. While this intake pattern has a reasonable distribution throughout the waking hours, amino acid availability is potentially low during the night.

This begs the question: does protein distribution throughout the day matter for muscle protein synthesis?

Several studies suggest that protein should be reasonably distributed for optimal anabolism. For example, an even balance of protein intake at breakfast, lunch and dinner stimulates MPS more effective than eating the majority of daily protein during the evening meal (Marerow, 2014). But a too high distribution resulting in many mini snacks may also be suboptimal. Providing 20 g of protein every 3 hours stimulates MPS more than providing the same amount of protein in less regular doses (40 g every 6 hours), or more regular doses (10 g every 1.5 hour) (Areta, 2013).

While there are more studies that support the concept of protein distribution, there are even more studies that suggest it has no clear benefit. If your goal is to absolutely maximize gains, it theoretically makes sense to try to aim for at least a reasonable protein distribution (3-4 protein rich meals divided throughout the day). But the impact of protein distribution is likely going to be small at best and you definitely don’t have to set a timer for each meal.

PS: I have some new data on this topic that I can’t share yet….but….it’s exciting 😉

7.9 Muscle full effect

The muscle full effect is the observation that amino acids stimulate MPS for a short period, after which there is a refractory period where the muscle does not respond to amino acids. More specifically, after protein intake, there is an lag period of approximately 45-90 min before MPS goes up and peaks between 90-120 minutes, after which MPS returns rapidly to baseline even if amino acid levels are still elevated (Bohe, 2001)(Atherthon, 2010).

The muscle full effect has given birth to a theory on how to optimize protein intake throughout the day in the online fitness community. It suggests that after amino acids levels have been elevated, you should let them drop down back to fasting levels to sensitize the muscle to amino acids again. Subsequently, protein intake will stimulate MPS again.

There is no evidence to support this theory.

The suggested mechanism seems unlikely as many food patterns result in elevated amino acid levels throughout the whole day. The traditional bodybuilding diet consists of very frequent, very high protein meals (e.g. chicken, rice, broccoli 6 times a day). In fact, it was specifically designed with the goal of keeping amino acids elevated throughout the whole day so there would always be enough building blocks for form new muscle tissue. Or intermittent fasting where all daily protein is eaten in a short time period (usually 8 hours).

These diets would only allow for a single ~90 min increase in MPS during a whole day. Clearly, that’s not what’s happening as these approaches are used by many with great success to improve muscle mass.

More likely, there’s a refractory period and it simply takes some time before the muscle responds to AA again. You don’t have to let amino acids drop to sensitize the muscle.

However, the relevance of the muscle full effect can be questioned in athletes.

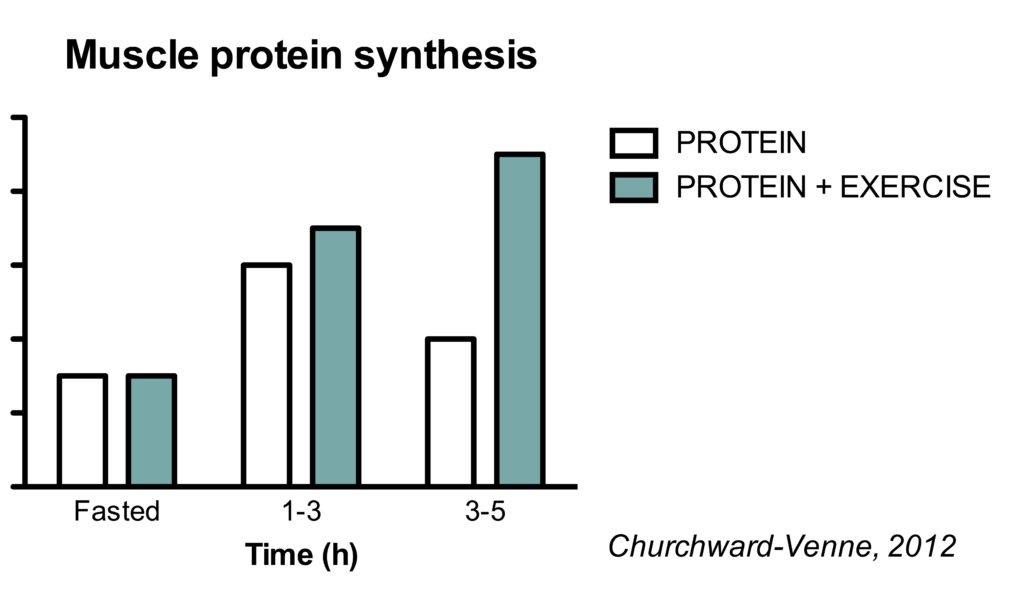

This is best illustrated in a study where the effect of protein was assessed in both rested and post-exercise conditions (Churchward-Venne, 2012).

Protein intake alone stimulates MPS in the 1-3 h period after ingestion. Subsequently, MPS rates fall back to basal rates. However, in post-exercise condition, protein stimulated MPS rates in both the 1-3 h and the 3-5 h period.

It appears that the muscle full effect is not present in acute post-exercise conditions. It’s interesting to note that resistance exercise can increase the sensitivity of the muscle to protein for at least 24 h (Burd, 2011).

The muscle full effect is an interesting phenomenon, but we don’t understand it well enough to let it influence our protein intake recommendations.

7.10 Protein prior to sleep

As discussed above, an effective protein distribution optimizes MPS. Therefore, it makes sense to eat protein just prior to overnight sleep, the longest period you can’t eat. 40 g of protein prior to sleep increases MPS during overnight sleep (Res, 2012). Protein supplementation (27.5 g) prior to sleep during a 12-week resistance training program improves muscle mass and strength gains (Snijders, 2015).

7.11 Energy intake

Only three days of dieting already reduce basal MPS (Areta, 2014). This shows that an energy deficit is suboptimal for MPS, however you can grow muscle mass while losing fat (Longland, 2016). It is unclear if eating above maintenance is needed to optimize MPS.

8. Summary

- While muscle protein breakdown is an important process, it doesn’t fluctuate much, which makes it far less important for muscle gains than muscle protein synthesis

- Whole-body protein synthesis is not really relevant for athletes. (often just called protein synthesis in studies, don’t confuse it with muscle protein synthesis)

- Muscle protein synthesis is predictive for muscle hypertrophy.

- Muscle protein synthesis studies are more sensitive to pick up anabolic effects than long-term studies measuring changes in muscle mass

- It’s easy to draw wrong conclusions if you don’t fully understand the methods.

How to optimize muscle protein synthesis: exercise guidelines:

- Train each muscle group at least twice a week with multiple sets

- Rep range doesn’t matter if you train (close?) to failure

- Rest at least 2 minutes between sets

How to optimize muscle protein synthesis: nutrition guidelines:

- Eat 4-5 meals spread throughout the day: e.g. breakfast, lunch, post-workout shake, dinner, and pre-sleep.

- Eat 20-40 g protein at each meal. Amounts above 20 g give a small additional benefit.

- Choose animal protein (whey protein is the best). Or compensate by eating larger amount of plant protein.

- If your main goal is to build muscle, eat at least maintenance calories.

Now I need your help.

Please bookmark this post for a couple of reasons:

First, I will keep this post updated with new research.

Second, I will continue to further elaborate sections based on your feedback and add additional sections in the future.

Lastly, please reference specific sections from this article when you see a discussion on muscle protein synthesis. People mistaking whole-body protein synthesis for muscle protein synthesis: see section 4.1. Someone skeptical about a conclusion from a paper because muscle protein breakdown was not measured? Section 2 buddy. Someone claiming that protein supplementation is not effective based on a long-term study he read that found no improvement in muscle mass: section 5 got you covered.

Feel free to ask me questions about the methods, or interpretation on protein metabolism studies in comments or on Facebook. If certain questions keep popping up I’ll rewrite the related sections to make it more clear for everyone.

![1-[13C]-leucine](http://www.nutritiontactics.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/1-13C-leucine.jpg)

A great review is better than most nutrition textbooks.

My question is about a plant-based diet like the Med diet and the optimal MPS. If we consume more than 1.6 gr/Kg/d PRO and with a decent distribution (4 meals) in a plant-based diet plus a well-designed RE program can we archive similar MPS rises, lean body mass and performances (lifts) in the average well train individual?

More specific case study: Do you think that an elite athlete in weight lifting can sustain a long-term peak performance with a plant-based diet (with the possibility of a protein supplement) but with a sufficient protein intake of more than 1.6 gr/kg/d ?

Great paper https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40279-021-01434-9

Yes.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3514209/

Hello Jorn in this study the distribution and the protein breakdown were a factor.

How do you look at a study like this, any validity to it?

Keep up the good work

Hi Alexander,

That study uses “poor” methodology. It can be used to test our an hypothesis, but on it’s own doesn’t carry much weight unless confirmed with better methods.

Protein distribution is an interesting topic. But looking at all the evidence on it, potential positive effects of protein distribution are likely small at best.

My stance on it: protein distribution is pretty easy to score well on (eat a decent amount of protein in 4 meals spread out throughout the day, e.g. breakfast, lunch, dinner, and pre-sleep). So why not try it? If you can’t do it or don’t want to do it, don’t worry about it. It probably won’t make a major difference anyway.

Thank you for this wonderful resource, Jorn!

My question:

What would you say is the minimum amount of food required to increase insulin enough to maximally inhibit muscle protein breakdown?

Reason for asking: Plenty of people aren’t hungry in the mornings and forcing food down your throat isn’t conducive to long-term adherence. Would something as little as 5g of EAAs mixed in water be suitable upon waking, just to make it to an MPS-stimulating dose of protein at breakfast 2-3 hours later?

I tend to eat in an 8-hour window naturally, which does seem to negate much of the MPS gains in my particular case. Shortening the breakdown period with the minimum viable dose feels like the path of least resistance.

About 20 g of whey protein or carbohydrates. For example, a banana.

I love this post. Just rereading it.

So comprehensive informative

This is a wonderful resource—thank you!

Intermittent fasting and muscle protein synthesis seems like an exciting but ambiguous area. Suppose someone is looking to maximize muscle protein synthesis while having the longest fasting periods possible. Suppose X represents recommended daily protein intake—in my case, about 180g—and Y recommends protein per meal, and it sounds like 20g yields the maximum marginal effect. Eating Y/X = 9 daily meals spaced 3 hours apart is clearly impossible in a 24 hour day, so it sounds like there will be inevitable efficiency losses due to higher protein amounts per meal (20g could be 40g or 60g) or shorter windows of time (that 3 hours could be 2 hours).

Are there any recommended practices or known constraints here, including for instance fasting for a day and having 6 meals of 60g each the next day (or spreading the protein out the rest of the week)? Fasted exercise followed by eating seems like an easy way to start.

Hi Nick,

I don’t you can compensate for fasted periods.

Suppose that you can have 100 anabolism in a day.

Scenario A:

Eating optimal protein for 2 days: 200 anabolism.

Scenario B:

day 1: fasted –> 0 anabolism

day 2: double protein intake –> 100 anabolism

average anabolism still only 100 (instead of 200).

Your maximal anabolism does not go up because you fasted before.

So I don’t think there is any specific guideline to follow. Fast when you want, and try to eat high protein during the other moments.

Hello and thank you for great text. But i now take pure leucine ~5g time to time, at the morning for example when i do not hungry, is it a good point to increase protein synthesis or it’s works with others aminoacids only?

It’s better than nothing, but you need the other EAA with it to be really effective. Even if you’re not hungry, a regular protein shake should be doable?

Jorn, Thanks for your great work and clear write up. One caveat. Most of the studies referenced were likely younger folks. I’m 63 and have read studies that 50 gs of protein is needed for MPS instead of the standard 20gs for younger folks. I’m currently at 17.5″ biceps at 5’8″ tall and about 23 months into my program. I recently added creatine. My focus now is maximizing MPS, nitric oxide and testosterone. (the later for muscle and bonners. lol) Any links you have to “old folks muscle” and NO2 or testoterone would be appreciated. Glad I ran across you!

Hey Bob,

No, the infographics we about older adults are all focused on protein:

https://www.nutritiontactics.com/elderly-have-lower-protein-digestion-and-absorption/

https://www.nutritiontactics.com/elderly-need-more-protein-for-muscle-growth/

https://www.nutritiontactics.com/pre-sleep-protein-beneficial-for-older-adults/

https://www.nutritiontactics.com/elderly-have-lower-protein-digestion-and-absorption/

But I’m sure we’ll cover those other topics at some point!

Thank you!

[SCIENTIFICALLY BACKED discourse below]

Hello Jorn, First off, thank you immensely. I mean how wonderful a detailed description for anyone seeking a better understand of the mechanistic action of the effect of nutrition and its “blow-by-blow” impact on muscle growth.

My main question and argument is: If mammalian muscle is only at best 23% by mass amino acids, where is the balance in maximizing protein intake for muscle maintenance and minimizing protein intake to balance mTOR activity to prevent accelerated aging? Phrased differently: Why do we need more than 103g/day of protein at any stage for 99.9% of all weight classes?

+++

I’m on the constant search for better answers for how to balance mTOR activation rather than over-activate it. mTOR (mTORC1 in particular) stimulates various transport signals into the cellular lysosome that accelerate DNA degradation (not just in muscles but in ALL cells, – see: https://www.karger.com/Article/Fulltext/484629).

With mTOR’s demonstrated impact on longevity in-vivo in mammalian models (mice, rats, primates, sadly, not humans!) begs the question, how much protein is too much? And so I am constantly searching for best practices re: protein intake.

Some basic facts to go along with the assessment

How much protein is in mammalian muscle? SOURCES –

https://www.depts.ttu.edu/meatscience/docs/Composition_Muscle_Structure.pdf,

https://www.hindawi.com/journals/tswj/2016/3182746/ (See Section 3, first paragraph)

All mammalian muscle, ALL, not just some, are composed of 18%-23% amino acids by mass (depending on the muscle). The rest of the “muscle” is composed of varying percentages of ash, mineral nutrients, fat & water.

That means even if a human gained 1lb (454g) of PURE MUSCLE per WEEK (that’s a person who is “jacked”), they’d only need about 91g (20% of 454) of protein per WEEK, ABOVE MAINTENANCE. That’s ~13g per day above maintenance.

But What is this magical “MAINTENANCE” level? The most hated response for most is that “it varies”. Unfortunately, it does depend on the mammal’s physical stage of growth, the NET daily metabolic caloric surplus/deficit as well as other less measurable (and for the 3-sigma of the population) far less critical factors (such as genetic makeup & epigenetic expression). For the sake of simplification, I’ll assume that a nutritional calorie’s energy is just one calorie, a reasonably good approximation, except for substantial consumers of fructose). SOURCE: On average, 99.99% of humans’ maintenance levels do not require more than 90g of protein per DAY. In fact, for 99% of the tallest human beings with the highest bone mineral density skeletal structures, they consumed 103g PER DAY (90g MAINTENANCE + 13g/day for muscle growth).

Anecdotally, I’m 170lb (5’10, DEXA Jan 2022: 16%) and I only eat about 0.8g/lb (slightly above the goal I’d like to get to for mTORC1 balance of 0.65g/lb). I am gaining lots muscle (~0.3lbs/week for the past 18 months at that level). So why do I need to over-activate mTOR?

I would really appreciate an answer so I can better understand what I am missing, learn and adjust accordingly!

Thank you again!

Hi Fadi,

I think you’re getting lost by overvaluing theoretical mechanistic data based that is also based on animal models.

Let’s simplify:

1) exercise is VERY healthy.

2) Exercise stimulates mTOR

3) Too much mTOR activation is suggested to be detrimental to health

See how the above does not really add up? The reason is that the molecular regulation of muscle mass, function, and longevity is VERY complicated, and poorly understood.

The research on longevity and especially the mechanisms behind it is very weak. We don’t have a good enough understanding on how total or specific amino acid intake impacts longevity and what the role of mTOR is in this.

In contrast, there is tons of research that exercise is healthy and that protein intake can help improve muscle mass gains. For aging, poor bodycomposition and frailty are much bigger risks than true longevitity concerns IMO.

Even IF too much protein intake stimulated mTOR activation would decrease total live span a bit, I would probably still consume a high protein diet. Because it will help maintain muscle mass and function, and allow you to function as you get older. I’m just making up numbers, but which scenario would you like better:

– Be able to walk to 90. Die at 95

– Be able to walk to 85. Die at 105

(again this is IF protein would decrease longevity. It could be easily argued that the increased muscle mass and function would increase longevity in real life)

This is further discussed in this review:

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26791164/

First off, really great insights!

I’m not sure if I may have missed this or if I’m not understanding this correctly, but is MPS specific to the muscle that you are training? For example, if I train my biceps on Monday, does the MPS signal get sent for just that muscle group or is it sent to the entire body? Thank you!

Hi Allen,

Thank you for kind words.

The effect of training on MPS is specific to the muscles you trained. If you train biceps on Monday, only MPS in the biceps will be stimulated.

The effect of protein on MPS is for all muscles.

Hi Jorn,

Thank you so much for this comprehensive article – the sheer amount of work you have put in to it is much appreciated!

1) Pre-sleep protein: Because casein is so slow to digest and doesn’t cause as much of a MPS peak as whey, is it possible to get the best of both worlds (i.e. large MPS peak and prolonged MPS time) by combining the two proteins before bed? If so, what amount of each would you recommend? Should the total amount of protein be kept at 40g or should an amount of whey be added on top of 40g of casein?

2) Probably a very stupid question: After a workout is MPS only increased in the muscles exercised or across the whole body? Will other muscles grow too? For example, if following a PPL split is MPS increased in your chest too after training the legs?

3) You mentioned to someone in the comments that glycogen stores are not appreciably depleted by resistance training. However, does consuming simple carbs still help with *general* fatigue/low energy levels during a workout? For example, if I’ve already eaten a good meal consisting of complex carbs and protein an hour or two before working out, will having a banana or a sugary soda drink immediately before or during exercise help me when I inevitably get tired halfway through my workout?

4) §7.8 Protein distribution: Any update yet on the exciting new data? Or at least a hint? 🙂

Hi Mike,

Thank you for the kind words.

1) I have a paper under submissions that compares pre-sleep casein vs whey. That will give some insight. Theoretically, a combination of whey and casein could be better than either of them alone. But I don’t think it would make much difference and I would not have 40 g of both, that is overkill. If you consume at least 40 g of either of them, you’ll get good results. Above that is very likely very diminishing returns that is not worth the effort for most people.

2) Only in exercised muscle.

3) If you had complex carbs 1-2 h before a workout, you’re likely still digesting that during the workout. But having some carbs during the will not hurt, so you might as well do it (but don’t feel like you need it).

4) No 😉

Hey Jorn. This is amazing, a personal MPS bible for me. I hope you are able to release further periodic updates/revisions to this as we uncover more insights.

I believe there is one error in your references. In section 5, in the second paragraph, you state, “. But the vast majority of long-term protein supplementation studies (80%) have found that protein supplementation does not increase muscle mass gains (Cermak, 2012).”

However, Cermak and colleagues have heavily advocated for the contrary of your statement.

Quotes:

– “Protein supplementation increases muscle mass and strength gains during prolonged resistance-type exercise training in both younger and older subjects”

– “Pooled estimates showed that protein supplementation during prolonged (>6 wk) resistance-type exercise training significantly augments the gains in FFM, type I and II muscle fiber CSA, and 1-RM leg press strength compared with resistance-type exercise training without a dietary protein based cointervention.”

– “Protein supplementation resulted in ∼1-kg greater gains in FFM after 12 ± 1 wk of resistance-type exercise training when compared with training without additional protein supplementation.”

Cermak and colleagues do mention that they did not find individual reports of significant gain in FFM in older groups, however they later mention, “Once the data were pooled, however, it became evident that dietary protein supplementation during resistance-type exercise training increased FFM by an additional 38% when compared with the placebo”

Cermak’s work actually presents one of the more bolder correlations between dietary protein supplementation and FFM gain / strength gain, so I do not think you did them justice. Perhaps you intended to cite another reference?

Hi Leo,

Cermak et al was the first convincing evidence that protein supplementation improves muscle mass gains.

But that doesn’t change anything about the statements I made in that section. Maybe you don’t realize, but Cermak and colleagues….are my colleagues! I was not involved in that specific publication, but I work with them and know exactly how they think about just about anything related to protein 😉

My statement is correct: the meta-analysis by Cermak shows that 80% of the studies found no significant effect of protein supplementation. You can see that in the forest plot in the publication. Everytime the “arms” are crossing the zero line, the study found no significant effect. However, when the data from all studies was combined, a significant improvement in muscle mass was observed. It might be confusing to you that 80% of the studies find no effect, yet when the data is combined the effect is significant. I’ve tried to explain why in that section. If you want to understand it better you would have to look up how meta-analysis work, which can be technical depending on how much statistical expertise you have.

Thanks for your response. Another question I have was in regards to this section:

“However, this study found that 40 g of protein resulted in approximately 20% higher higher MPS rates compared to 20 g.”

What study does “this study” refer to?

Thanks

It’s the last study that is discussed/referenced above it.

Macnaughton, 2016:

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27511985/

I see protien amount of “0.24 g/kg bodymass (or 0.25 g/kg lean body mass) would optimize muscle protein synthesis” with a later caveat of upping it to .40g.

So can we conclude .40g of protein per kg of lean body mass per day is enough for optimal muscle growth but if you want to go above optimal, add more protein?

What kind of gains is considered optimal?

Don’t take it to literal. There is no hard definition of “optimal”. With optimal, I mean the point after which a lot of extra effort is nog going to result in meaningful additional results.

How much gains that is in say kg muscle depends on 101 factors and is different for everyone.

Thank you for this really helpful article. I’m struggling with building muscle what would I need to ask my doc in order to get a better understanding of my muscle function and protein synthesis ?

Hi,

You want to ask your doc to get info on muscle function and protein synthesis? Doctors will only have a basic understanding of these things, they’re not going to be able to help you.

Honestly, knowledge can only help you so much. If you understand most of this article, other knowledge will have very little additive value. Just try to read what you can find online, but don’t expect too much from it. There are nog secrets out there. Just keep training and eating as good as you can.

I understand if it’s a disappointing answer, but it’s real.

Jorn

Great post! Thank you, Jorn.

Hello Jorn

Should there not be a distinction between rest and workout days with regards to protein intake?

Maybe.

Resistance exercise can stimulate MPS up to 72 h. So even the day after a training session, your MPS will be elevated. Theoretically, you can eat a bit less on non-training days. But I would play it safe and consume the same on non-training days.

Hey, John.

I’m a 6’1 male, weighing 168 lbs. Daily, I consume roughly 130g of protein, consuming roughly 3000 calories total, while also supplementing creatine, HMB and beta-alanine. I workout about 5 days weekly, and I’ve been doing the same workout for 3 months straight, which comprises push-ups, neutral grip pull-ups, dumbbell side lateral raises and bicep curls. And it’s also important to note that I do 3 sets per exercise with 3-5 minutes in between sets. However, what happens when cardio enters the equation? Will cardio negatively affect MPS and impede muscle growth? I’m a fencing athlete. But I want to build muscle too. Is that still possible with my current routine? Or do changes need to be made?

Sincerely, Daniel Cothran

Hey Daniel,

What you’re doing seem pretty good.

Cardio can negatively impact MPS/muscle growth. However, it depends on a variety of factors.

The more advanced you are, the more difficult it becomes to make additional muscle gain. So someone who has been doing building for years, will have to try to minimize cardio if they want to continue to progress. If people with a lot less resistance-training experience, cardio has much less negative effect.

The further your cardio is away from your resistance training, the better. Try to avoid doing both sessions directly after each other.

What type of cardio are you doing? Because if you run/cycle, that will mostly impact your legs. While your resistance-training is upper body.

So in your case, the cardio will have little no negative impact on muscle growth.

Many thanks!

As for your question, most of my cardio comes from fencing, which is HIIT cardio. Fencing is a total body exercise. The lower body, shoulder, lower back and core are all heavily used. After a fencing session, which I do at 7pm, I’m exhausted. I burn about 700-800 calories. But a good night’s rest seems to be enough for full recovery, and then I get into my home workout in the afternoon.

Question aside, I’ve gained 2 lbs of muscle in 7 days! Even while doing cardio and burning off a bit of fat! Now I weigh 170 lbs at 15% body fat. Must be newbie gains.

You mention that longer rest periods increased Muscle Protein Synthesis. How does this interact with supersets?

If I do biceps and triceps ‘back to back’ for example. I can keep 2-3 minutes between each muscle group being hit, but there would only be ~1 minute of rest between bouts of exercise. For the purpose of MPS would this count as 2+ minutes of rest or 1 minute of rest?

You count the rest periods per muscle group, not per exercise.

However, the example you give is not ideal. In many back exercises (pull downs/up, rows) you still use your your biceps quite heavily. For example, a row and barbell curl superset does not give the biceps optimal rest because both hit the biceps. In contrast, bench press and biceps curl work well together.

Happy new year Jorn!

I found out about you from your podcast with Jeff Nippard. Really loved the way you explained things!

I am really confused when taking a look at this from a plant-based perspective. In the podcast, you said that the main ideas about the plant-based diet is that, generally speaking, plant-based protein may lack certain amino acids–especially leucine.

Let’s say a person required 100g daily protein to build muscle (using the 1.6 g/kg of body weight).

Would this mean that a person who ate 100g of his daily protein from steak vs someone who ate 100g daily protein from tofu, theoretically have stimulated MPS better because steak has a superior amino acid profile?

In the podcast you said that to compensate, plant-based lifters could simply just eat more plant protein and mix different sources of plant-based proteins to make up for deficiencies in certain amino acids. But, how would you even do this practically?

If you do need to eat more protein, how much more grams of protein from tofu would you need to equal the MPS stimulation from that 100g of protein from steak?

This is difficult for me to understand because then I feel like I would have to track the amount of EACH amino acid and make sure they all reach their optimum amounts/thresholds–especially for leucine.

Is there an easy way to track the amino acids of your foods? As easy as logging in your calories?

Hi Enzo,

Happy new year!

Yes, theoretically you would need to make sure you have enough of all the essential amino acids. Tracking it would be quite difficult. A more simple approach is just to consume 25% more protein to compensate for the lower AA content and digestibility of plant-based protein.

However, a recent study suggested that at a protein intake of 1.6 g/kg there was no difference in muscle mass gains between vegans and meat eaters. There are ofcourse all kind of discussion points we could get into for that study, but I think it does show that at relatively high protein intakes (≥1.6 g/kg) plant protein diet will give similar results to a more animal-based diet. During suboptimal protein intake, the lower protein quality might be a bigger issue.

Thank you for giving me some practical recommendations Jorn! It really helps me as I try to build some gains in the plant-based direction. Speaking of which, are there any other special considerations for someone following a plant-based diet? Will there be a section for that in this article?

I would also love to know exactly how you came up with the recommendation of 25%, was there a study somewhere? And regarding your study where 1.6 g/kg of bodyweight was recommended. Is that study cited somewhere in this article already? I wasn’t able to find it.

Hello Jorn. Fantastic article!

To piggyback on a question from Christopher below in June:

For optimum body recomposition why would one not simply take advantage of the critical time “windows” you have elucidated?

1: MPS 24-36 hrs

2: Muscle degradation minimum 72 hrs following energy deficit

3: Minimum 2 RE days per week.

1: Enter into slight but sufficient energy surplus on the two RE days with appropriate protein intake schedule. Continue x 24 to 36 hours.